10.1 Screening for ß2-microglobulin amyloidosis, including measurement of serum levels of ß2-microglobulin, is not recommended. (OPINION)

10.1a No currently available therapy (except kidney transplantation) can stop disease progression of ß2-microglobulin amyloidosis or provide symptomatic relief. (EVIDENCE)

10.1b Kidney transplant should be considered to stop disease progression or provide symptomatic relief in patients with ß2-microglobulin amyloidosis. (EVIDENCE)

10.1c In patients with evidence of, or at risk for, ß2-microglobulin amyloidosis noncuprophane (EVIDENCE), high-flux dialyzers (OPINION) should be used.

ß2-microglobulin amyloidosis (Aß2M) (also referred to as dialysis-related amyloidosis [DRA] or dialysis-associated amyloidosis) is a serious, debilitating complication affecting patients with end-stage renal disease. This disorder is characterized by amyloid deposits with ß2-microglobulin fibrils as the major protein, primarily affecting joints and periarticular structures. The clinical manifestations include carpal tunnel syndrome, spondyloarthropathies, hemarthrosis, and joint pain and immobility.325,326 Late in the disease course, systemic deposition can occur principally in the gastrointestinal tract and heart.327-329 While mortality from Aß2M is rare, the disease can cause significant morbidity and is a major cause of joint pain and immobility in patients on long-term dialysis. The disease is most commonly reported in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis therapy, but has also been observed in patients treated exclusively by CAPD or prior to the initiation of dialytic therapy.326,330-332

ß2-microglobulin is a nonglycosylated polypeptide of 11,800 Da. The principal site of metabolism of ß2-microglobulin is the kidney.333 In normal individuals, the serum concentration of ß2-microglobulin is less than 2 mg/L. However, ß2-microglobulin serum levels in dialysis patients are 15 to 30 times greater than normal. The pathophysiology of the disease is not clear, but most experts agree that the accumulation of ß2-microglobulin over time is important. The manifestations of Aß2M gradually appear over the course of years, between 2 and 10 years after the start of dialysis in the majority of patients (see below). In one series, 90% of patients had pathological evidence of Aß2M at 5 years.334 However, many patients may have the disease pathologically, but do not manifest clinical symptoms. In addition, the clinical symptoms are often nonspecific, and easily mistaken for other articular disorders. All of these factors make Aß2M particularly difficult to diagnose clinically.

Given the significant morbidity that Aß2M causes in patients with end-stage renal disease, the Work Group focused on three major questions:

(1) What is the best diagnostic technique?

(2) What are the potential therapies that slow the progression, prevent, or symptomatically treat the disease?

(3) Is screening for the disease practical, and if so, when should it begin?

The “gold standard” diagnostic technique is a biopsy demonstrating positive Congo Red staining and immunohistochemistry for the presence of ß2-microglobulin. Thus, to answer the first question, alternative diagnostic techniques compared to biopsy as the “gold standard” were assessed. To answer question 2, studies evaluating potential therapies for Aß2M have aimed to reduce the serum level of ß2-microglobulin, remove or debulk the amyloid deposit, or reduce inflammation that may contribute to the development of the disease. Multiple clinical end points were evaluated in the search for therapies, including fractures, carpal tunnel syndrome, bone pain and mobility, and spondyloarthropathy. Although dialysis is not an exclusive cause of Aß2M as previously thought, it is plausible that differences in dialysis membranes may either (1) increase the removal of ß2-microglobulin and thus be a potential therapy; or (2) may cause increased inflammation and generation of ß2-microglobulin, and thus contribute to or exacerbate the disease process. Thus, in evaluating the potential contribution of dialysis membranes to Aß2M, multiple end-points were evaluated, including serum levels of ß2-microglobulin and clinical end-points. Lastly, in order to assess whether screening for the disease was practical, the answers to the preceding questions and the natural history of the disease were considered.

Because many patients with pathological evidence of the disease do not manifest clinical symptoms, and the disease progresses over several years, Aß2M is particularly difficult to diagnose or study. Ideally, appropriate clinical trials would require large numbers of patients followed for several years. Unfortunately, there are limited prospective trials. There were many available retrospective or case-control studies that fulfilled the evidence report inclusion criteria, but this design presents a particular problem in evaluating a slowly progressive disease due to changes in the dialysis procedure and medications over time. In addition, depending on how the cohort was defined (ie, pathological evidence, long-term dialysis patients, or those with clinical symptoms), there could be considerable bias. Thus, the overall strength of the evidence is weak. Nevertheless, some evidence-based Guidelines could be established from publications that meet the inclusion criteria established by the Work Group.

Diagnostic Tests

To best answer the question of whether there are good alternative diagnostic tests to biopsy, an ideal design would be a direct comparison of these diagnostic techniques to pathological evidence of the disease by biopsy. However, of the 10 studies evaluating alternative diagnostic tests that met the inclusion criteria for evaluation,335-344 only 3 utilized joint biopsy.336-338 The rest compared the diagnostic technique with clinical symptoms, or presence of pathological evidence of the disease elsewhere (eg, carpal tunnel syndrome). Five studies on scintigraphy,336,339-342 4 studies of shoulder ultrasound,337,338,343,344 and 1 study of MRI335 were examined using the best available evidence. All of these studies reported that these alternatives worked well. However, most studies suffer from small sample size, lack of controls, and bias. The latter is usually in the form of predominantly enrolling patients with more severe forms of the disease, prohibiting the calculation of true sensitivity/specificity for these tests. Thus, the applicability of these studies to the general dialysis population is unknown. Furthermore, the ability to diagnose and differentiate ß2-microglobulin deposits from other causes of joint abnormalities will also be dependent upon the experience of the reader for each specific test. For example, the ability to diagnose Aß2M by MRI will be greatest with an experienced radiologist. It should also be noted that scintigraphy results may be affected by which carrier protein is labeled, and these are not readily available in the United States. Thus, despite the apparent usefulness of these various diagnostic tests in these studies, further confirmation is required, and biopsy remains the "gold standard." Based on a single study that looked at differences in biopsy sites, the sternoclavicular joint appeared to be the most sensitive location in assessing the pathological presence of Aß2M.345

Role of Dialysis Membrane

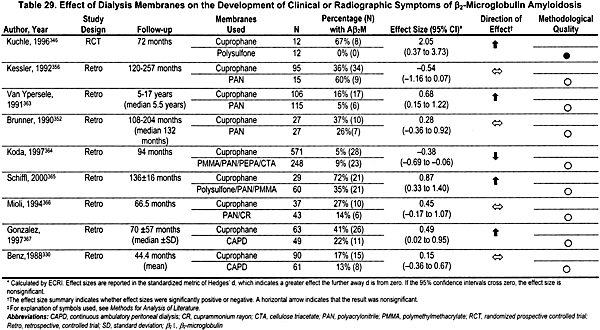

To determine the effect of dialysis membranes on the incidence and severity of ß2-microglobulin, 21 studies evaluating the effect of one or more membranes on clinical, biochemical, and radiological evidence of Aß2M were identified that fulfilled the inclusion criteria: 5 long-term, prospective studies,346-350 10 retrospective studies,133,330,351-356 and 6 trials looking at the ability of different membranes to remove ß2-microglobulin from the blood over the course of 1 to 5 dialysis sessions.357-362 None of these trials used any blinding. Unfortunately, of these 5 prospective trials, only 3 were randomized,346,347,350 and only 1 of these looked at clinical signs and symptoms and had adequate follow-up.346 Most studies evaluating various membranes have directly compared exclusive or near-exclusive use of cellulosic membranes such as cuprophane to noncellulosic, semi-synthetic, high-efficiency, or high-flux dialyzers. Several, but not all, studies have demonstrated a benefit of the noncellulosic membranes, with at least 1 clinical end-point (Table 29), but a meta-analysis could not be done comparing cellulosic versus other membranes due to heterogeneity. However, for the single end-point of prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome, polyacrylnitrile membranes were superior to cuprophane membranes by meta-analysis.352,356,363 The only prospective, randomized, controlled trial346 found that patients dialyzed with polyacrylnitrile membranes had less carpal tunnel syndrome, fewer bone cysts, and decreased thickness by shoulder ultrasound compared to patients dialyzed with cuprophane.

Five long-term prospective controlled trials and seven retrospective studies addressed the effect of different dialysis membranes on serum ß2-microglobulin levels. The reported results from the studies and the results of the exploratory meta-analyses are summarized in Table 30. Due to the low number of trials for each membrane, and the heterogeneous nature of the results, summary effect sizes could not be calculated for most of the different membranes. Three out of four trials, including a high-quality, randomized, controlled trial, found that dialysis with polysulfone membranes removes more ß2-microglobulin from the serum than dialysis with cuprophane membranes. CAPD, Gambrane, Hemophan, PMMA, and EVAL membranes were all reported to remove more ß2 microglobulin from the blood during dialysis than dialysis with cuprophane membranes.

Two retrospective trials reported no significant difference in the prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients dialyzed with CAPD as compared to patients on hemodialysis with cuprophane membranes.330,367 One retrospective trial reported that patients on CAPD had significantly lower rates of spondyloarthropathy and bone cysts than did patients on cuprophane hemodialysis.367 CAPD was reported to result in lower ß2-microglobulin serum levels than did cuprophane hemodialysis. The low number and poor quality of the studies of CAPD must be kept in mind when interpreting these results.

Fig 13. Summary odds ratio of being diagnosed with Aß2M over time on dialysis.

Screening

No studies that met the inclusion criteria of the Evidence Report addressed the question of how often, if ever, patients should be screened for Aß2M. An optimal approach to ascertaining when screening for Aß2M should begin would be to conduct a prospective cohort study in which a group of typical kidney failure patients were followed from the time that they commenced maintenance dialysis and were screened frequently for the onset of Aß2M. Only 1 study has approached this ideal trial design.369 In this study, 15 patients were retrospectively followed for over 15 years on dialysis. The other 16 studies addressing this question are cross-sectional studies.334,344,345,368,370-380 They are retrospective in that they selected groups of patients who had been on hemodialysis for some time (time on dialysis is retrospective), and then prospectively examined them for signs and symptoms of Aß2M (detection of the disease is prospective). A problem with this study design is that the incidence of Aß2M cannot be determined because it is unclear when exactly each patient began to develop Aß2M. Only prevalence of the disease can be determined from a cross-sectional trial. Another difficulty with this study design is that it may be inadvertently including a rather special group of patients—only those who remained on dialysis for long periods of time at the same center were included in the trial (ie, patients who died, received kidney transplants, or relocated were not included in the trial). Thus, the evidence is not optimal.

These study limitations not withstanding, a summary odds ratio of the prevalence of Aß2M was calculated using meta-analysis. An odds ratio of 1.0 indicates no cases; the larger the odds ratio, the more likely it is that all patients will have disease. After 2 years on hemodialysis, the summary odds ratio is 16.82 (95% CI, 5.75 to 49.17). After 5 years on hemodialysis, the summary odds ratio is 15.32 (95% CI, 5.12 to 45.83). After 10 years on hemodialysis, the summary odds ratio is 51.85 (95% CI, 15.11 to 177.86). After 15 years on hemodialysis, the summary odds ratio is 114.13 (95% CI, 16.49 to 789.96). The natural logarithm (ln) of the summary odds ratio is graphed versus time on dialysis in Fig 13. These results, in combination with considerations about the effectiveness of treatment for Aß2M, can be used to determine when screening for Aß2M should begin. However, for screening for Aß2M to be rational, there would need to be an effective therapy for the disorder.

Therapies

Unfortunately, there are limited studies evaluating therapy, none of which are controlled and all of which have short term follow-up which, given the slow progression of the disease, may overestimate the efficacy of a specific therapy. Seven studies evaluated kidney transplant as a therapy,351,381-386 two before and after transplantation.383,384 As expected, kidney transplantation led to lower serum levels of µ2-microglobulin. In addition, joint mobility and bone pain improved, but X-ray findings and spondyloarthropathy did not improve, suggesting the deposits do not regress. Prednisone therapy improved bone pain and joint mobility, but only one small trial meeting criteria was available.384 A study describing 11 patients who underwent surgical removal of amyloid deposits demonstrated improvement in joint mobility and bone pain, but follow-up was short.387lang1033 Two other studies evaluated the use of ß2-microglobulin adsorbent columns run in series with standard dialysis.388,389 These columns lowered serum levels of ß2-microglobulin, but clinical symptoms were not evaluated. Clearly these data are weak and should be considered preliminary due to small sample size and limited follow-up. In addition, none of the studies reported the use of any kind of blinding, resulting in substantial bias. Further complicating the interpretation of these studies is the variety of end-points evaluated in the different studies. Thus, these studies would suggest that kidney transplantation is the only effective therapy to avoid the morbidity of Aß2M. However, given that a functional kidney transplant is a preferred therapy for kidney failure for a number of reasons, it is unlikely that transplantation will be prescribed only for the purpose of treating Aß2M. For this reason, the Work Group recommended that routine screening of patients for the presence of Aß2M not be done.

The lack of quality studies in this field may be reflective of the slow progressive nature of the disease as well as the discordant relationship between clinical symptoms and pathological evidence of the disease. All of these factors produce significant limitations on the quality of the data. In addition, there was considerable bias in patient selection and very few studies had adequate and rigorous controls. Thus, the strength of the evidence supporting this Guideline is weak.

The Work Group agreed that Aß2M is a significant cause of musculoskeletal morbidity in dialysis patients. The Work Group also agreed that many of the available diagnostic techniques could demonstrate ß2-microglobulin amyloid, as could a clinical examination, although the true specificity and sensitivity of the available diagnostic test are unknown. The data evaluating dialysis membranes is of sub-optimal quality; however, the Work Group felt the data at least supported the observation that non-cuprophane membranes may slow the progression of the disease. The lack of conclusive data supporting the use of noncellulosic dialysis membranes or peritoneal dialysis, led the Work Group to—at this time—recommend that noncellulosic membranes be utilized only in patients who have a life expectancy on dialysis greater than 2 years, as this appears to be the earliest time-point that there is evidence for Aß2M. However, there may be reasons other than the prevention of, or slowing the progression of, Aß2M to use noncellulosic membranes such as issues associated with biocompatibility. Continued research into membranes or dialysis techniques that remove more ß2-microglobulin is needed. Routine screening for Aß2M is not recommended, as the only potential therapy is kidney transplantation and it is unlikely that transplantation will be prescribed only for the purpose of treating Aß2M.

Long-term studies of the role of various dialysis membranes and other novel therapies are clearly warranted. However, the overall mechanism of the pathogenesis of the disease also requires further research so that more specific therapies can be developed.