Click on Image to view full size

THE OVERALL AIM of the project was to develop guidelines for the assessment and treatment of dyslipidemias in patients with CKD, irrespective of the underlying cause of the kidney disease.

The Work Group sought to base guidelines as much as possible on the evidence, derived from a systematic summary of the available scientific literature on dyslipidemia in patients with CKD.

Two products were developed from this process: a set of clinical practice guidelines regarding assessment and treatment of dyslipidemia, which is contained in this report; and an evidence report, which consists of the summary of the literature. Portions of the evidence report are contained in this report. The entire evidence report is on file with the National Kidney Foundation.

The guidelines were developed using 4 basic principles set forth by KDOQI:

Development of the guideline and evidence report required many concurrent steps to:

Creation of Groups

The Co-Chairs of the KDOQI Advisory Board selected the Work Group Chair and Director of the Evidence Review Team, who then assembled groups to be responsible for the development of the guidelines and the evidence report, respectively. These groups collaborated closely throughout the project.

The Work Group consisted of "domain experts," including individuals with expertise in nephrology, nutrition, pediatrics, transplantation medicine, epidemiology, and cardiology. In addition, the Work Group included a liaison member from the Renal Physicians Association. The first task of the Work Group members was to define the overall topic and goals, including specifying the target condition, target population, and target audience. They then further developed and refined each topic, literature search strategy, and data extraction form (described below). The Work Group members were the principal reviewers of the literature, and, from these detailed reviews, they summarized the available evidence and took the primary roles of writing the guidelines and rationale statements.

The Evidence Review Team consisted of nephrologists and methodologists from Tufts-New England Medical Center with expertise in systematic review of the medical literature. They were responsible for managing the project, including: coordinating meetings; refining goals and topics; creating the format of the evidence report; developing literature search strategies, initial review and assessment of literature; and coordinating all partners. The Evidence Review Team also managed the methodological and analytical process of the report. Throughout the project, and especially at meetings, the Evidence Review Team led discussions on systematic review, literature searches, data extraction, assessment of quality of articles, and summary reporting.

Development of Topics

Based on their expertise, members of the Work Group selected several, specific topics for review. These included the incidence or prevalence of dyslipidemia in CKD, the association of dyslipidemia with ACVD, and the treatment of dyslipidemia in patients with Stage 5 CKD (including kidney transplant recipients). For patients with Stages 1-4 CKD, topics were limited to adverse effects of dyslipidemia treatment, the effects of dyslipidemia treatment on kidney disease progression, and the effects of therapies that reduce proteinuria on dyslipidemias. The Work Group employed a selective review of evidence: a summary of reviews for established concepts (review of textbooks, reviews, guidelines and selected original articles familiar to them as domain experts); and a review of primary articles and data for new concepts.

The overall target population for guidelines on the management of dyslipidemia included all people with CKD (Stages 1-5), including all patients with kidney transplants. However, the Work Group concluded that the recently updated guidelines of the National Cholesterol Education Task Force, Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III),3 are applicable to patients with Stages 1-4 CKD. Therefore, the recommendations of ATP III would not need to be modified for patients with Stages 1-4 CKD, except to: (1) classify these patients in the highest risk category; (2) consider complications of lipid-lowering therapies that may result from reduced kidney function; (3) consider whether there may be indications for the treatment of dyslipidemias other than preventing ACVD; and (4) determine whether the treatment of proteinuria might also be an effective treatment for dyslipidemias. Therefore, for Stage 1-4 CKD patients, the Work Group focused its attention on the latter three issues, and otherwise recommended that the ATP III Guidelines be followed in patients with Stages 1-4 CKD. Likewise, the Work Group chose not to include children and adolescents (<20 years old) with Stages 1-4 CKD, who should be managed with existing guidelines, such as those of the National Cholesterol Expert Panel on Children (NCEP-C).

The Work Group concluded that in most areas the ATP III and NCEP-C were applicable to adults and children, respectively. The Work Group considered that its task was to define areas where the ATP III and NCEP-C needed modification and refinement for patients with CKD.

Refinement of Topics and Development of Materials

The Work Group and Evidence Review Team developed (a) draft guideline statements, (b) draft rationale statements that summarized the expected pertinent evidence, (c) mock summary tables containing the expected evidence, and (d) data extraction forms requesting the data elements to be retrieved from the primary articles to complete the tables. The development process included creation of initial mock-ups by the Work Group Chair and Evidence Review Team followed by iterative refinement by the Work Group members. The refinement process began prior to literature retrieval and continued through the start of reviewing individual articles. The refinement occurred by e-mail, telephone, and in-person communication regularly with local experts and with all experts during in-person meetings of the Evidence Review Team and Work Group members.

Data extraction forms were designed to capture information on various aspects of the primary articles. Forms for all topics included study setting and demographics, eligibility criteria, causes of kidney disease, numbers of subjects, study design, study funding source, population category (see below), study quality (based on criteria appropriate for each study design; see below), appropriate selection and definition of measures, results, and sections for comments and assessment of biases. Training of the Work Group members to extract data from primary articles subsequently occurred by e-mail as well as at meetings.

Assessment of Dyslipidemias

Evidence supporting guideline statements regarding the assessment of dyslipidemias was sought in published studies on (1) the prevalence of dyslipidemias in CKD; (2) the association between dyslipidemias and ACVD; and (3) the association between dyslipidemias and CKD progression. To ascertain the prevalence of dyslipidemias in CKD, the Work Group and Evidence Review Team examined retrospective and prospective cohort studies. To ascertain the association between dyslipidemias and ACVD or CKD progression, the Work Group and Evidence Review Team examined retrospective and prospective cohort studies, as well as case-control studies.

Treatment of Dyslipidemias

Evidence supporting guideline statements regarding the efficacy of treatment of dyslipidemias was sought only in randomized controlled trials of patients with CKD. Direct and indirect evidence on the safety of treatment of dyslipidemias in CKD was sought in controlled and uncontrolled studies of (1) the pharmacokinetics of lipid-lowering medications in CKD; (2) possible drug interactions in CKD; and (3) possible adverse reactions to lipid-lowering therapies in CKD (including small series and case reports).

Literature Search

The Work Group and Evidence Review Team decided in advance that a systematic process would be followed to obtain information on topics that relied on primary articles. Only full journal articles of original data were included. Review articles, editorials, letters, or abstracts were not included.

Studies for the literature review were identified primarily through MEDLINE searches of English language literature conducted between December 2000 and May 2001. These searches were supplemented by relevant articles known to the domain experts and reviewers.

The MEDLINE literature searches were conducted to identify clinical studies published from 1980 through the search dates. Studies prior to 1980 were disregarded, because the Work Group concluded that treatment modalities and methods to measure dyslipidemias have changed too much to reasonably conclude that evidence from studies prior to 1980 could be applicable today.

Separate search strategies were developed for each topic. Development of the search strategies was an iterative process that included input from all members of the Work Group. The text words or MeSH headings for all topics included kidney or kidney diseases, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplant. The searches were limited to studies on humans and published in English. The MEDLINE search strategies are included in the Evidence Report.

The topics that were selected for the searches included the incidence or prevalence of dyslipidemia, the association of dyslipidemia with ACVD, the association of dyslipidemia with CKD progression and the treatment of dyslipidemia in patients with Stage 5 CKD (including kidney transplant recipients). For patients with Stages 1-4 CKD, topics for the literature retrieval were limited to adverse effects of dyslipidemia treatment, the effects of dyslipidemia treatment on kidney disease progression, and the effects of therapies that reduce proteinuria on dyslipidemias. The team did not conduct a systematic search for all studies on dyslipidemia prevalence, association with ACVD and treatment for patients with Stages 1-4 CKD.

MEDLINE search results were screened by clinicians on the Evidence Review Team. Potential papers for retrieval were identified from printed abstracts and titles, based on study population, relevance to topic, and article type. In general, studies with fewer than 10 subjects were not included. After retrieval, each paper was screened to verify relevance and appropriateness for review, based primarily on study design and ascertainment of necessary variables. Domain experts made the final decision for inclusion or exclusion of articles. All articles included were abstracted and incorporated in the evidence tables. Overall, 10,363 abstracts were screened, 642 articles were retrieved and reviewed by the Evidence Review Team, 258 articles were reviewed by members of the Work Group, and results were extracted from 133 articles, including a number of articles not located by the MEDLINE searches, but added by Work Group members.

Format for Evidence Tables

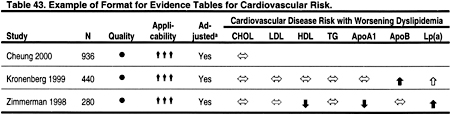

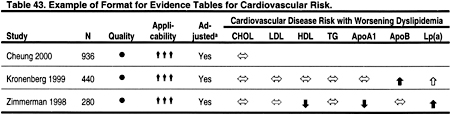

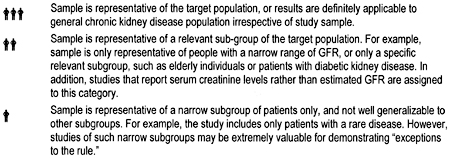

Two types of evidence tables were prepared. Detailed tables contain data from each field of the components of the data extraction forms. These tables are contained in the Evidence Report, but are not included in the manuscript. Summary tables describe the strength of evidence according to four dimensions: study size, applicability depending on the type of study subjects, methodological quality, and results. Within each table, studies are ordered first by methodological quality (best to worst), then by applicability (most to least), and then by study size (largest to smallest). Two examples of evidence tables are shown in Tables 43 and 44.

Click on Image to view full size

Click on Image to view full size

Study Size

The study (sample) size is used as a measure of the weight of the evidence. In general, large studies provide more precise estimates of prevalence and associations. In addition, large studies are more likely to be generalizable; however, large size alone does not guarantee applicability. A study that enrolled a large number of selected patients may be less generalizable than several smaller studies that included a broad spectrum of patient populations.

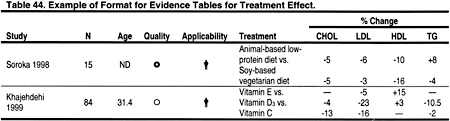

Applicability

Applicability (also known as generalizability or external validity) addresses the issue of whether the study population is sufficiently broad so that the results can be generalized to the population of interest at large. The study population is typically defined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The target population was defined to include patients with chronic kidney disease, except where noted. A designation for applicability was assigned to each article, according to a 3-level scale. In making this assessment, sociodemographic characteristics were considered, as were the stated causes of chronic kidney disease, and prior treatments. If study was not considered not fully generalizable, reasons for lack of applicability were reported.

Individual tables include columns with relevant data describing the study sample and thus the applicability of the study. Examples include mean age (in years), kidney replacement therapy modality (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, transplant) and type of kidney disease (eg, diabetes, hypertension).

Click on Image to view full size

Results

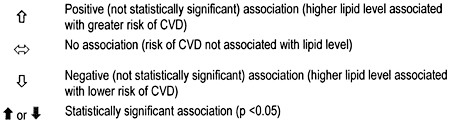

In principle, the study design determined the type of results obtained. For studies of association of dyslipidemia and CVD the result is direction and strength of the association between level of dyslipidemia and risk of CVD. Associations are represented according to the following symbols:

Click on Image to view full size

For randomized trials of treatment effect and for studies of prevalence of dyslipidemia, results are reported as the percent change in lipid level from baseline for each treatment examined, or for the percentage of subjects with each type of dyslipidemia (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides).

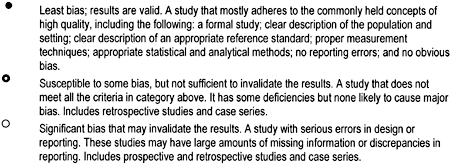

Quality

Methodological quality (or internal validity) refers to the design, conduct, and reporting of the clinical study. Because studies with a variety of types of design were evaluated, a 3-level classification of study quality was devised:

Click on Image to view full size

Summarizing Reviews and Selected Original Articles

Work Group members had wide latitude in summarizing reviews and selected original articles for topics that were determined, a priori, not to require a systematic review of the literature. The use of published or derived tables and figures was encouraged to simplify the presentation.

Translation of Evidence to Guidelines

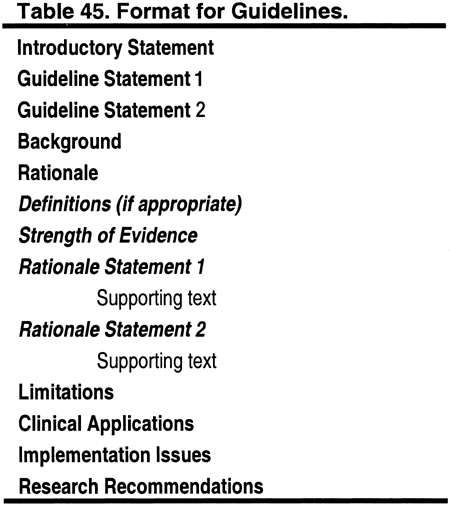

Format

This document contains 5 guidelines. The format for each guideline is outlined in Table 45. Each guideline contains 1 or more specific "guideline statements," which are presented as "bullets" that represent recommendations to the target audience.

Click on Image to view full size

Each guideline contains background information, which is generally sufficient to interpret the guideline. A discussion of the broad concepts that frame the guidelines is provided in the preceding section of this report. The rationale for each guideline contains a series of specific "rationale statements," each supported by evidence. The guideline concludes with a discussion of limitations of the evidence review and a brief discussion of clinical applications, implementation issues, and research recommendations regarding the topic.

Strength of the Evidence

The Work Group rated the strength of each guideline using a modification of a system originally adopted by the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination.445 Accordingly, recommendations were graded A, B, or C (Table 7) when:

Health outcomes are conditions or health-related events that can be perceived by individuals to have an important effect on their lives. Improving net health outcomes implies that benefits outweigh risks, and that the action is cost-effective. The strength of evidence was assessed taking into account (1) methodological quality of the studies; (2) whether or not the study was carried out in the target population, ie, patients with CKD, or in other populations; and (3) whether the studies examined health outcomes directly, or examined surrogate measures for those outcomes, eg, improving dyslipidemia rather than reducing CVD (Table 8).

Limitations of Approach

While the literature searches were intended to be comprehensive, they were not exhaustive. MEDLINE was the only database searched, and searches were limited to English language publications. Manual searches of journals were not performed, and review articles and textbook chapters were not systematically searched. However, important studies known to the domain experts that were missed by the literature search were included in the review, as were essential studies identified during the review process.

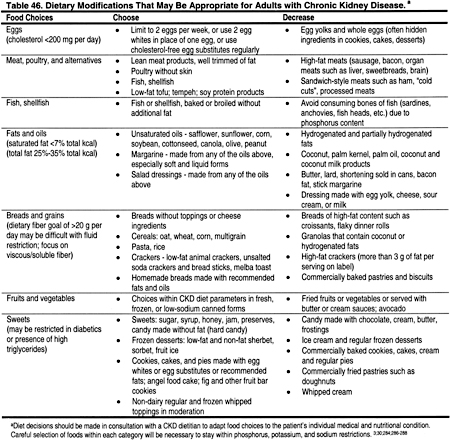

Comprehensive nutrition counseling should be offered to all patients with CKD, given the high incidence of malnutrition and other nutritional abnormalities. Detailed guidelines of the KDOQI Nutrition Work Group for adults and children recommend a regular assessment of nutritional status and intervention by a renal dietitian.446 However, dietary management of patients with dyslipidemias is not specifically addressed in the KDOQI nutrition guidelines. Therefore, the Work Group made the following recommendations (Table 46).

Click on Image to view full size

During the initial assessment and subsequent follow-up of patients with CKD, it is important to assess malnutrition and protein energy deficits. If the patient is well nourished, dietary modifications for dyslipidemias can be undertaken safely. In some patients with CKD, standard CKD diet recommendations may have already appropriately reduced many foods with high unsaturated fats such as milk products.

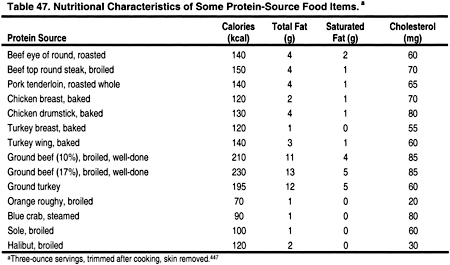

It is important to consider patients with low total cholesterol. A low total cholesterol level, especially in association with chronic protein-energy deficits and/or the presence of comorbid conditions, may signal malnutrition. Patients with cholesterol <150 mg/dL (<3.88 mmol/L) should be assessed for possible nutritional deficiencies. For patients with malnutrition or protein-energy deficits, improving nutrition should be the primary goal. Dietary recommendations may include high-protein foods, with a liberal intake of foods high in saturated fat. However, in the majority of cases, acceptable protein sources low in saturated fat should be encouraged (Table 47). Low-fat dairy products, nuts, seeds, and beans may provide protein, but potassium and phosphorus contents should still be limited.

Click on Image to view full size

Overall, healthy food preparation should be encouraged, such as using peanut, canola, or olive oil in cooking, since these are high in monounsaturated fats.

Plant Sterols

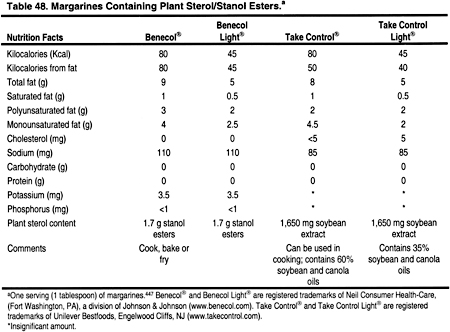

Plant sterols block the absorption of cholesterol from the small intestine by entering into micelles, which are needed for cholesterol to dissolve. Consequently, endogenous and dietary cholesterol becomes insoluble, and is therefore excreted in the stool. Plant sterols themselves are not absorbed or excreted well. Studies in the general population have shown that the intake of 2-3 g of plant sterols per day lowers LDL by 6% to 15%, with minimal change to HDL or triglycerides.3 Reductions in LDL have been seen in hypercholesterolemic children448,449 and adults.450-452 The use of esters needs to take into account daily total fat consumption, and adjustments in caloric intake may also be needed. There is no contraindication to the use of plant sterols in patients with CKD; however, they should be used as a fat substitute and not for other therapeutic reasons. Unfortunately, some commercial products are expensive (Table 48).

Click on Image to view full size

Fiber

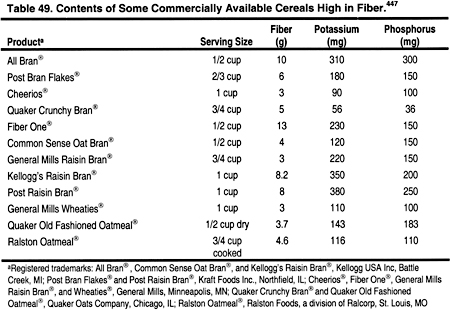

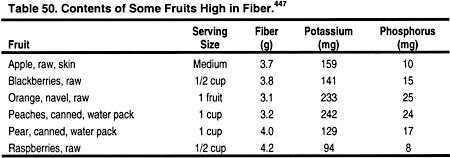

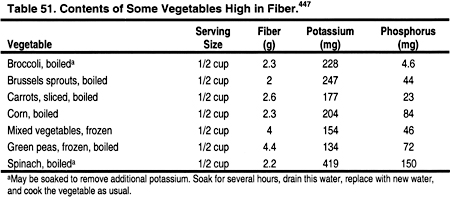

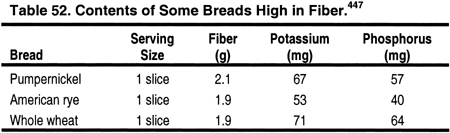

Viscous fiber should be increased by 5-25 g per day to help reduce total cholesterol and LDL.3 High-fiber diets require additional fluid intake, which may be difficult for the anuric dialysis patient who is often limited to 1 L of fluid per day. Many high-fiber foods are also restricted in the renal diet due to their high phosphorus and/or potassium content. These foods may have to be included more often, and the phosphate binder or potassium content of the dialysate may need to be adjusted, to maintain normal serum phosphorus and potassium. Since each company varies the ingredients in their brands, it is essential to read nutrition labels, and to use those lowest in potassium and phosphorus. For example, a 1-cup portion of Kellogg’s Raisin Bran (Kelloggs, Battle Creek, MI) has less potassium and phosphorus than Post’s Raisin Bran® (Kraft Foods, Inc., Northfield, IL). Common foods containing natural fiber are described in Tables 49, 50, 51, and 52.

Click on Image to view full size

Click on Image to view full size

Click on Image to view full size

Click on Image to view full size

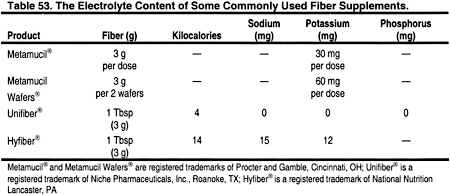

Patients who are unable to consume adequate fiber through their diet can add natural fiber in the form of a tasteless powder to their meals (Table 53). Psyllium is a viscous fiber recommended by the ATP III.3 The most common commercial product is Metamucil® (Proctor and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH).

Click on Image to view full size

It should be mixed with 8 oz of fluid per dose, which may be difficult due to strict fluid restrictions in the dialysis patient. Magnesium may also be an excipient in some psyllium products, and those should be avoided. Sugar-free products are available for use in diabetics. Psyllium is also made generically, and it is imperative to review the product insert before use to ensure that it contains low amounts of potassium, sodium, and magnesium. Unifiber® (Niche Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Roanoke, TX) contains powdered cellulose, corn syrup solids and xanthan gum, and can easily be blended into applesauce, Cream of Wheat, or 3-4 fluid ounces of apple juice or water to provide 3 g of natural fiber. These products do not interfere with the absorption of medications or vitamins. Constipation is a chronic problem for dialysis patients who are restricted in the actual amount of fiber and fluid they can consume. Osmotic agents such as Polyethylene Glycol 3350, NF Powder, eg, Miralax® 17 g orally (Braintree Laboratories, Braintree, MA) or other products, may be needed to relieve constipation.