NKF KDOQI GUIDELINES

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations

2006 Updates

Hemodialysis Adequacy

Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy

Vascular Access

I. CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR PERITONEAL DIALYSIS ADEQUACY

CLINICAL PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION FOR GUIDELINE 1: INITIATION OF KIDNEY REPLACEMENT THERAPY

There is variability with regard to when a patient should be started on dialysis.

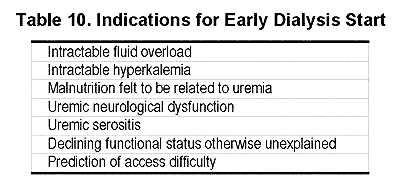

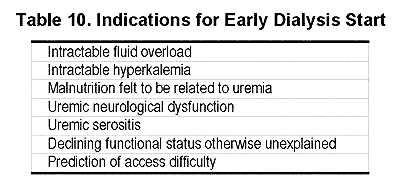

1.1 Kidney replacement therapy may be started earlier for a variety of reasons, as outlined in Table 10.

1.2 Uremic cognitive dysfunction can affect learning. Therefore, the initiation of home-based self-dialysis may need to occur at an earlier point than that for center-assisted dialysis.

1.3 Kidney replacement therapy may be delayed if the patient is asymptomatic, is awaiting imminent kidney transplant, is awaiting imminent placement of permanent HD or PD access, or, after appropriate education, has chosen conservative therapy.

- 1.3.1 If KRT is delayed, the patient should be re-evaluated on a regular basis to determine when KRT should be initiated.

- 1.3.2 Nephrologists should actively participate in the care of patients who choose conservative therapy, and should consider conservative treatment of kidney failure as an integral part of their clinical practice.

- 1.3.3 If, for any reason, KRT is not instituted, patients with estimated GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 should be re-evaluated by a nephrologist at frequent intervals.

1.4 Choice of modality:

- 1.4.1 Patients who choose PD for their modality should not be required to have a HD access placed. However, venous sites for possible future HD access in the arms should be preserved since many patients require multiple modalities during their remaining lifetime.

- 1.4.2 Patients who chose cycler dialysis for lifestyle reasons can begin dialysis without an intervening period on CAPD; however, some programs may wish to train all patients on the CAPD technique for various reasons.

1.5 In the patient with significant RKF, consideration may be given to an incremental start of dialysis, i.e., less than a “full” dose of PD.

RATIONALE

Kidney replacement therapy may be started earlier for a variety of reasons (see Table 1).

Patients with advanced cardiomyopathy have been initiated on dialysis at a GFR greater than 15 mL/min successfully. Such an approach may decrease the length of hospitalizations and improve QOL.173A-173F There are no data that this may prolong survival, but an improvement in QOL would seem sufficient to utilize this approach.

In 2000, NKF KDOQI published clinical practice guidelines addressing the management of nutrition in CKD.35 These guidelines updated and partially revised the DOQI Peritoneal Adequacy Guidelines of 1997 that recommended the imitation of dialysis based on nutritional deterioration due to uremia. Also in 2000, the PD Adequacy Work Group revised its 1997 Guidelines to include as its Guideline 2, the verbatim Guideline 27 of the Nutrition Guidelines specifically describing the imitation of dialysis based on nutritional indications.35 The 2005 PD Adequacy Work Group recognizes these previous guideline and refers readers to them. Since 2000, any publications addressing this issue have corroborated the earlier observations as described in the 2000 Nutrition Guidelines.

Uremic cognitive dysfunction can affect learning. Therefore, the initiation of home dialysis may need to occur at an earlier point than that for center-assisted dialysis.

The patient who chooses home dialysis, whether it be home HD, cycler PD, or CAPD, generally is the one who is to learn the procedure. Therefore, it becomes important to plan the start of dialysis carefully such that the patient is not so sick that he or she cannot adequately learn the procedure. If this is not done properly, the patient will require a period of time on in-center HD. This is undesirable for a number of reasons. First of all, this often means the patient will have a HD catheter, which is a very significant risk factor for bacteremia (a much higher risk than a PD catheter). Secondly, the time on HD may impair RKF. Thirdly, this may strain the resources of the HD program. Planning for training also requires coordination with the home-training nurses, as there may be limited resources available. In some cases (e.g., children, or those with a helpful and willing spouse), the learner is someone who is not uremic. In these cases, it is not quite as important to begin the training early.

Kidney replacement therapy may be delayed if the patient is asymptomatic, is awaiting imminent kidney transplant, is awaiting imminent placement of permanent HD or PD access, or, after appropriate education, has chosen conservative therapy. If KRT is delayed, the patient should be re-evaluated on a regular basis to determine when KRT should be initiated.

Given the risk of starting dialysis with a tunneled HD catheter, if the patient is completely asymptomatic and access placement is imminent, it would seem reasonable to delay the start of dialysis until more permanent access can be placed, either an arteriovenous fistula or PD catheter. Some patients refuse the option of dialysis and are not suitable transplant candidates. Such patients may change their minds as kidney failure progresses and symptoms increase. Therefore, it is important to closely follow such patients.

Patients who choose PD for their modality should not be required to have a HD access placed.

Many patients who start PD have, as their ultimate goal, kidney transplantation. As such, the patient may be on PD only a relatively short time (measured in years) prior to transplantation. It would seem unreasonable in such cases to expose the patient to the risk of placement of HD access. For those patients who appear likely to fail PD in the future, formation of an arteriovenous fistula in a timely manner may appear reasonable; however, there are limited data on who might be at risk for PD failure.

Patients should not be required to first train for CAPD if planning to perform cycler therapy at home.

After receiving information about PD, patients often have strong opinions on whether they prefer CAPD or the cycler for home dialysis. In some cases the cycler is chosen because of convenience, work schedule, or because a partner is helping the patient. Thus, if this is the patient’s modality choice, it would seem reasonable to train the patient on the cycler from the start. The program may chose to subsequently train the cycler patients on manual exchanges as a back-up plan if electricity fails, or if a mid-day exchange is added.

In the patient with significant RKF, consideration may be given to an incremental start of dialysis, i.e., less than a “full” dose of PD.

A working definition of incremental dialysis is the addition of any type of dialysis in defined doses over time to achieve a prescribed total clearance which is achieved by the combination of dialysis plus RKF. It can refer to the addition of one type of dialysis to another as well as any type of dialysis to RKF.173G,173H This concept has been utilized for a long time and can be considered individualization of therapy by mixing and matching therapies to a specific set of circumstances. The stage was set for this approach in 1985,173Iand numerous variations have been applied with success since.173J-173N The original 1997 DOQI Peritoneal Adequacy Guidelines endorsed this approach in the correct setting. In particular, patients have to understand the concept and clearly intend to comply with the addition of greater dialysis doses as RKF declines. This is addressed in the education program described above and, in the case of home dialysis, further accentuated during the home-training process. There may be logistical (e.g., travel distance), economic, psychological, social, or even medical reasons to attempt incremental dialysis. It is feasible and well described, but may not be suitable for all patients. Furthermore, some clinicians feel that more dialysis is better than less, regardless of RKF, so they recommend full-dose dialysis from the onset.

LIMITATIONS

The data are very limited in many of the areas discussed. For example, intractable volume overload in patients with cardiomyopathy may be managed with isolated ultrafiltration. This approach would appear to have significant risk to RKF. Studies comparing peritoneal approaches, such as using a single exchange with icodextrin for such patients, to isolated repeated ultrafiltration have not been performed.

IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

Monitoring of patients in whom dialysis is delayed may be difficult if the resources are not available. Given the increasing shortage of nephrologists in the face of increasing numbers of patients with advanced kidney failure, new approaches are needed. One approach might be to use renal nurse practitioners and physician assistants, to closely follow patients in whom the decision to defer dialysis has been made. Protocols could be constructed to trigger referral for start of dialysis in such situations.