Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of kidney failure in the United States. Diabetic kidney disease is characterized by the early onset of albuminuria, hypertension, and a high risk of coexistent or subsequent CVD.

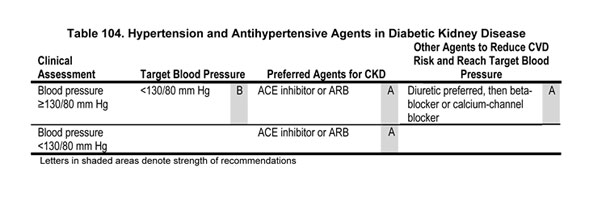

8.1 Target blood pressure in diabetic kidney disease should be <130/80 mm Hg (see Guideline 7) (Table 104).

8.2 Patients with diabetic kidney disease, with or without hypertension, should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB (Table 104).

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of kidney failure in the United States395 and is among the most common causes in the rest of the world. The natural history of diabetic kidney disease is characterized by the onset of albuminuria (microalbuminuria), hypertension, and declining GFR. Kidney pathology is similar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes, as is the natural history, with the exception of onset of hypertension and vascular disease earlier in the course of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes than in type 1 diabetes.396,397

A large number of epidemiological studies and controlled trials have defined risk factors for progression of diabetic kidney disease, and response to treatment.1 The purpose of this Guideline 8 is to review this rapidly expanding literature and translate the results into guidelines for clinicians.

Definitions

Clinical features of diabetic kidney disease, by stage, are shown in Table 105. For this guideline, we included studies in type 1 and type 2 diabetes with CKD Stages 1-4. Studies of kidney transplant recipients are included in Guideline 10. For evaluation of CVD outcomes, we extrapolated from studies in the general population (Guideline 7). We also included studies of CVD in individuals with diabetic kidney disease.

Because of the high prevalence of diabetes in the population, many individuals with other types of CKD may also have diabetes. In general, the guidelines for use of antihypertensive agents in kidney disease due to diabetes and due to other causes do not conflict.5,398

For this guideline, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are compared to other classes of antihypertensive agents. There are few studies directly comparing these two classes to each other in diabetic kidney disease, and no comparative outcome studies. In these studies, diuretics were frequently used as an additional antihypertensive agent to achieve blood pressure control. In addition, some data are provided comparing other classes of antihypertensive agents.

Entries in summary tables comparing antihypertensive agents are grouped first by diagnosis (type 1 versus type 2 diabetes), then by agent (ACE inhibitors first), then by control group medications (placebo then active control groups), then by methodological quality (highest first), then by applicability (widest first), then by study size (largest first). Entries in summary tables comparing blood pressure targets are grouped first by diagnosis (type 1 versus type 2 diabetes) then by methodological quality (highest first), then by applicability (widest first), then by study size (largest first).

Most patients with diabetic kidney disease are hypertensive (Strong). Prevalence of hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg) in diabetic kidney disease is shown in Table 106. The onset of hypertension in type 1 diabetes generally signifies the onset of kidney disease. In contrast, hypertension in type 2 diabetes may occur in the absence of kidney disease.

Higher levels of blood pressure are associated with more rapid progression of diabetic kidney disease (Strong). A number of prospective studies show a strong relationship between a higher level of blood pressure and an increased risk of kidney failure and worsening kidney function in diabetic kidney disease.112,404,405 Some studies suggest that higher SBP is more important than higher DBP or high pulse pressure for kidney disease progression.404,406

Multiple antihypertensive agents are usually required to reach target blood pressure (Strong). Table 107 shows the target and achieved SBP and the number of antihypertensive agents used in randomized trials of antihypertensive agents to slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease. Multiple agents were usually required.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are effective in slowing the progression of kidney disease with microalbuminuria due to type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Strong). ACE inhibitors and ARBs lower urine albumin excretion, slow the rise in albumin excretion and delay the progression from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria in kidney disease due to type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Table 108).335,339,409-417 Follow-up in these studies was generally in the range of 2 to 4 years, so in most studies GFR was stable and there was no difference in GFR decline between the ACE inhibitor or ARB groups and control groups.Because of the long duration of follow-up necessary to ascertain an effect of interventions on GFR decline in a study of patients with microalbuminuria, and the proven beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in later stages of diabetic kidney disease (see later in Guideline 8), the Work Group considered that these studies provided "strong" evidence, even though they are based on a surrogate endpoint.

Because of the early stage of kidney disease, some patients in these studies were not hypertensive. Consequently, patients in the ACE inhibitor or ARB group had lower mean blood pressure during follow-up than patients in the control group. In some studies, the beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors or ARBs appeared greater than the difference in mean follow-up blood pressure or persisted after adjustment for follow-up blood pressure in multiple regression analysis, suggesting that the benefit is due to mechanisms in addition to the antihypertensive effect. An individual patient meta-analysis of 646 patients in 10 randomized clinical trials confirmed these results.418 Consequently, the Work Group concluded that ACE inhibitors and ARBs are preferred agents for diabetic kidney disease with microalbuminuria and should be prescribed for patients with or without hypertension.

ACE inhibitors are more effective than other antihypertensive classes in slowing the progression of kidney disease with macroalbuminuria due to type 1 diabetes (Strong). A number of high-quality RCTs demonstrate that ACE inhibitors are more effective than other antihypertensive classes in reducing albuminuria and in slowing the decline in GFR and onset of kidney failure in subjects with macroalbuminuria329,419-421 (Table 108). Figure 37 shows the results from the Collaborative Study Group (CSG) trial of Captopril in Diabetic Nephropathy. In that study, the beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors was greater in patients with reduced GFR at baseline, possibly because the endpoint, a doubling of baseline serum creatinine, is achieved more quickly in patients with reduced GFR. The benefit was due in part to the antihypertensive effect of captopril and in part to additional mechanisms.

Fig 37. Collaborative Study Group (CSG) Captopril Trial. Change in blood pressure (A) and proteinuria (B). (Squares) Captopril group; (circles) placebo group. Cumulative event rates for doubling of baseline serum creatinine (C) and for death, dialysis, or transplantation (D). Modified with permission.329

Fig 38. Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT). Kaplan-Meier curves of the percentage of patients with the primary composite end point (A) and its individual components, a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration (B), end-stage renal disease (C), and death from any cause (D). Reprinted with permission.139

ARBs are more effective than other antihypertensive classes in slowing the progression of kidney disease with macroalbuminuria due to type 2 diabetes (Strong). A number of high-quality RCTs demonstrate that ARBs are more effective than other antihypertensive drug classes in slowing the decline in GFR and onset of kidney failure in subjects with albuminuria (Table 108). Figures 38 and 39 show the results from Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT) and the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL), two large, recent studies of patients with macroalbuminuria at the time of enrollment.139,338 In these studies, the beneficial effect of ARBs was due in part to their antihypertensive effect, and in part to additional mechanisms.

Fig 39. Reduction of endpoints in NIDDM with the angiotensin II antagonist losartan (RENAAL). Kaplan-Meier curves of the percentage of patients with the primary composite end point (A) and its individual components, a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration (B), end-stage renal disease (C), and the combined end point of end-stage renal disease or death (D). Reprinted with permission.338

ACE inhibitors may be more effective than other antihypertensive classes in slowing the progression of kidney disease with macroalbuminuria due to type 2 diabetes (Weak). There are conflicting data on the efficacy of ACE inhibitors in kidney disease due to type 2 diabetes. Some studies show greater reduction in albuminuria and slowing the decline in GFR337,420,426,427 (Table 108). However, the small sample size, the use of surrogate outcomes, and inconsistent results on surrogate outcomes preclude definitive conclusions. In contrast, a recent analysis of the large subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes and estimated GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 enrolled in ALLHAT showed no beneficial effects of an ACE inhibitor (lisinopril) compared to a diuretic (chlorthalidone) on decline in GFR or onset of kidney failure over a 4-year interval when each agent was used separately.293

As discussed in Guideline 7, it is the opinion of the Work Group that the ALLHAT results do not rule out a beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors on kidney disease due to type 2 diabetes. Instead, based on the shared properties of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in inhibiting the RAS, it may be extrapolated that ACE inhibitors may be as effective as ARBs and more effective than other antihypertensive classes in slowing the progression of kidney disease due to type 2 diabetes. Thus, it is the opinion of the Work Group that either ARBs and ACE inhibitors can be used to delay the progression of kidney disease due to type 2 diabetes with macroalbuminuria.

ARBs may be more effective than other antihypertensive agents in slowing the progression of kidney disease with macroalbuminuria due to type 1 diabetes (Weak). There are insufficient data on the efficacy of ARBs in kidney disease due to type 1 diabetes. The Work Group found no long-term, controlled trials on the use of ARBs in patients with kidney disease due to type 1 diabetes. However, based on the shared properties of both drug classes in inhibiting the RAS, it may also be extrapolated that ARBs may be as effective as ACE inhibitors and more effective than other antihypertensive classes in slowing the progression of kidney disease due to type 1 diabetic kidney disease. Thus, it is the opinion of the Work Group that ARBs can be used as an alternative class of agents to slow kidney disease progression if ACE inhibitors cannot be used.

Diuretics may potentiate the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in diabetic kidney disease (Moderately Strong). Between 60% and 90% of patients in studies of kidney disease progression in diabetic kidney disease studies used either thiazide-type or loop diuretics in addition to ACE inhibitors or ARBs.139,329,338,407 In contrast, diuretic use in the ACE inhibitor group of ALLHAT was restricted by protocol; only 18% of this group received a thiazide diuretic. Other studies have shown that the combination of agents that block the renin-angiotensin system with thiazide diuretics is more effective than either agent alone for lowering blood pressure.428-430 As discussed above, most patients with diabetic kidney disease require more than one antihypertensive agent to reach the target blood pressure of <130/80 mm Hg. It is the opinion of the Work Group that most patients with diabetic kidney disease should be treated with a combination of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB with a diuretic to reach the target blood pressure.

Fig 40. Meta-analysis of studies of diabetic and nondiabetic kidney disease. The left panel shows weighted mean results and 95% CIs for change in proteinuria in studies of antihypertensive agents. The effects of ACE inhibitors and nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers were significant. The right panel shows results of regression models. Coefficients are mean and 95% confidence interval for the change in proteinuria (%) for factors/number of studies. Only the effect of ACE inhibitors was significant. Reproduced with permission.431

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers have a greater antiproteinuric effect than other antihypertensive classes in diabetic kidney disease (Strong). Two meta-analyses have demonstrated a greater effect of ACE inhibitors compared to other classes of antihypertensive agents on reducing proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease431,432 (Figs 40 and 41). Other studies show a larger effect of ARBs compared to other classes.433-435 Nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers consistently demonstrate reductions in proteinuria.435a Some studies also suggest that beta-blockers may be effective, but this has not been observed consistently.436

Fig 41. Meta-analysis of studies of diabetic and nondiabetic kidney disease. Effects of blood pressure lowering agents in diabetic and nondiabetic renal disease. Depicted are the weighted mean results with 95% CIs for proteinuria (bars) and blood pressure (bold print) that have been obtained in studies that compared the effects of an ACE inhibitor to that of another blood-pressure lowering agent. On the left the results obtained with ACE inhibitors are shown subdivided to the type of renal disease (nondiabetic renal disease [nonDM] and diabetic nephropathy [DM]). Results obtained with the comparator drugs are given on the right. Reproduced with permission.432

Antiproteinuric effects of antihypertensive agents appear to be additive. The addition of a nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker to an ACE inhibitor can lead to further reduction in proteinuria.360 The combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB can reduce proteinuria more than either agent alone.425,437,438 Whether the benefits of combination therapy is additive or synergistic (greater than sum of all agents) is difficult to determine due to uncertainties of the maximum antiproteinuric effect of single agents.

Based on these data, it was the opinion of the Work Group that it would be reasonable to use a combination of a nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker and an ACE inhibitor or ARB or a combination of an ACE inhibitor and ARB to reduce proteinuria in hypertensive patients. Use of combinations of agents could also be considered in patients whose blood pressure is controlled using a single agent, but with persistent spot total protein-to-creatinine ratio >500 to 1,000 mg/d.

Dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers are less effective than other agents in slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease (Strong). Numerous studies show that dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers are less efficacious than ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in reducing albuminuria in diabetic kidney disease.439 IDNT and RENAAL showed that the dihydropyridine amlodipine was less effective in slowing kidney disease progression than the ARBs irbesartan and losartan, respectively.139,338 IDNT also compared amlodipine to a control group treated with placebo and other agents, primarily diuretics and beta-blockers.139 GFR decline and onset of kidney failure was similar in both groups, but the amlodipine group had higher levels of proteinuria.

In contrast, ALLHAT showed no detrimental effect of amlodipine compared to chlorthalidone on GFR decline or onset of kidney failure in type 2 diabetes when each agent was given separately.293 However, as discussed earlier, the small sample size in the ALLHAT diabetic CKD subgroup precludes definitive conclusions. Based on all these studies, and the results in nondiabetic kidney disease (Guideline 9), it was the opinion of the Work Group that dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers should not be used in diabetic kidney disease in the absence of therapy with an ACE inhibitor or ARB. It was the opinion of the Work Group that dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers may likely be used safely in patients taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB.406

An SBP goal even lower than <130 mm Hg may be more effective in slowing the progression of diabetic kidney disease (Weak). A meta-analysis of eight trials in diabetic kidney disease and four trials in nondiabetic kidney disease suggests that a lower blood pressure goal may slow progression of kidney disease (Fig 42). This analysis is limited by the inability to control other factors related to rate of progression. Some studies have addressed a lower blood pressure goal, independent of antihypertensive drug class (Table 109). These studies suggest that lower blood pressure levels are associated with lower levels of proteinuria. One study demonstrated a greater reduction in proteinuria in ramipril-treated patients randomized to a lower blood pressure goal (MAP <92 mm Hg, equivalent to blood pressure <125/75 mm Hg), compared to a usual blood pressure goal (MAP <107 mm Hg, equivalent to blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg).419 The ABCD trial showed a trend toward greater slowing of GFR decline at the lower achieved SBP of 128 mm Hg.407,423 Studies in nondiabetic kidney disease (reviewed in Guideline 9) suggest a lower blood pressure goal is more effective in slowing kidney disease progression in patients with proteinuria. Since diabetic kidney disease is accompanied by proteinuria, it was the opinion of the Work Group that a lower blood pressure goal may be beneficial for diabetic kidney disease as well. There is insufficient evidence to define this lower blood pressure goal or the threshold level of proteinuria above which the lower blood pressure goal is indicated. For consistency with recommendations in nondiabetic kidney disease (Guideline 9), it was the opinion of the Work Group that an SBP goal even lower than <130 mm Hg should be considered for patients with total protein to creatinine ratio >500 to 1,000 mg/g. Lowering of SBP levels to <110 mm Hg should be avoided.

Fig 42. Blood pressure level and rate of GFR decline in controlled trials of diabetic kidney disease. Diamonds represent the mean achieved systolic blood pressure and mean rate of calculated or directly measured GFR decline in the studies of diabetic kidney disease. Results not adjusted for other factors associated with rate of decline in GFR. The dotted line represents a flattening of possible benefit of BP lowering at BP levels below 140 mm Hg. Reproduced with permission.440

Comparisons With Other Guidelines

Due to the inclusion of new trials, Guideline 8 differs from older guidelines, but is consistent with the recent practice guidelines of the American Diabetes Association398,440a and JNC 7.5,5a Both of these guidelines support the use of diuretics with either ACE inhibitors or ARBs as initial therapy to achieve the SBP goal of <130 mm Hg in patients with diabetes. Moreover, JNC 7 defines hypertension in individuals with kidney disease or diabetes as blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg. The guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension also recommend use of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB for those with diabetes and kidney disease.441

Figure 43 and Table 110 summarize recommendations in diabetic kidney disease.

Fig 43. Hypertension and antihypertensive agents in diabetic kidney disease. Superscripts refer to items in Table 110.

These recommendations need to be qualified based upon the available data. First, no claims of superiority between ACE inhibitors and ARBs can be made since no randomized trials have compared these agents "head-to-head" in slowing the progression of kidney disease. Second, efficacy of therapy in many studies of diabetic kidney disease with microalbuminuria, efficacy of antihypertensive agents was based on reduced risk of kidney disease progression, as assessed by development of macroalbuminuria, rather than decline in GFR or onset of kidney failure.339 It is not practical, however, to conduct studies for the duration of follow-up required to observe a reduction in GFR decline or onset of kidney failure in patients with microalbuminuria; this would take more than 20 years of follow-up. Consequently, evidence from such studies was graded "strong." Moreover, since the level of albumin excretion in normotensive patients with diabetic kidney disease generally does not exceed "microalbuminuria," the recommendation for treating patients without hypertension is graded as "A."

Multiple interventions are required to slow progression of kidney disease and reduce the risk of CVD events in diabetic kidney disease. Generally, the approach requires three or more antihypertensive agents, intensive insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes, two drugs for glucose control in type 2 diabetes, at least one lipid-lowering agent, and emphasis on lifestyle modification including diet and exercise must be employed. One obstacle to achieving adherence is the number of medications. Therefore, the selection of antihypertensive agents must also include considerations of cost, side-effects, and convenience.

The coordination of care using a team approach can improve diabetic kidney disease; achievement of goals for glucose, lipids, blood pressure, diet, and other lifestyle modifications led to substantial benefits.104 In a long-term follow-up study, the intensive-therapy group had a significantly lower risk of CVD by 53%, progression of kidney disease by 61%, retinopathy by 58%, and autonomic neuropathy by 63%. Therefore, a strong commitment to reducing development of morbid events mandates increased time and effort by a variety of health-care professionals.

The following questions require additional study in diabetic kidney disease: What is the optimal dose of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for kidney disease protection? What is the possible protective role of ARBs and other classes of antihypertensive agents, either alone or in combination with ACE inhibitors, on slowing kidney disease progression and CVD? The question regarding the optimal level of blood pressure reduction for cardiovascular risk reduction will be answered in 2008 by the ACCORD trial. However, this may not answer the question about the optimal level of blood pressure to slow diabetic kidney disease progression. Finally, studies are needed to examine the relationship between magnitude of albuminuria reduction and reduction in kidney disease progression and CVD risk, and to determine the optimal "target value" for urine albumin excretion in diabetic kidney disease during treatment with ACE inhibitors and ARBs.