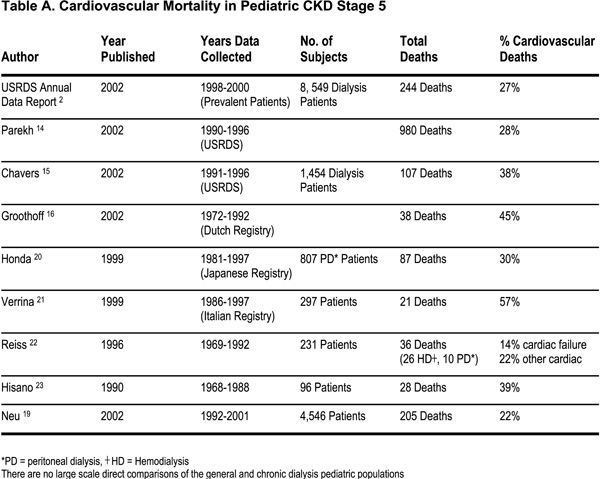

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients on chronic dialysis; it is now reported as either the first or second most common cause of death in series evaluating mortality in children on chronic dialysis (Tables A and B).2,14–17 Children and young adults on chronic dialysis have traditional factors leading to cardiovascular risk (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and physical inactivity). In addition, they have uremia-related risks such as anemia, volume overload, hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperparathyroidism, hypoalbuminemia, inflammation, and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (Table C). Large-scale, multicenter studies of risk factor outcomes for CVD in patients on chronic dialysis have not been carried out in the pediatric population. Guidelines for routine screening and monitoring of many of these risk factors are not in place for pediatric chronic dialysis patients. The data presented here support the need for prevention as well as greater recognition and treatment of CVD and CVD risk factors in children and young adults on chronic dialysis.

The Work Group considered whether to include children and adolescents in these guidelines as the majority of guidelines were directed to symptomatic atherosclerotic CVD. Children who are dialysis-dependent (Stage 5 CKD) are at risk of CVD; however, the spectrum of CVD does differ from that in adults. The guidelines proposed for children and adolescents under age 18 address the current state of knowledge in pediatric CKD Stage 5. If there are guidelines already provided for specific cardiovascular conditions or risk factors, we refer to the appropriate recommendations.

Data from the USRDS suggest that children aged 0–19 years make up 1% of known chronic dialysis patients in the U.S.17 Between 1998 and 2001 there were, on average, 2,199 children each year on chronic dialysis. Recent studies have shown that pediatric chronic dialysis patients bear a significant CVD burden and that CVD-associated mortality is 1,000 times higher in pediatric chronic dialysis patients than the nationally reported pediatric cardiovascular death rate.14 The highest cardiovascular death rate occurs in young children on dialysis who are <5 years of age. Transplantation in children lowers the risk of cardiovascular mortality by 78%; however, the rate of CVD mortality continues to be greater than that in the general pediatric population.14 The leading cause of mortality in the general pediatric population is accidents.18 Strategies to reduce CVD morbidity and mortality are clearly warranted in the pediatric CKD Stage 5 population.

Cardiovascular Disease Mortality (Strong)

In the 2002 USRDS data, CVD (defined as acute myocardial infarction, pericarditis, atherosclerotic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, valvular heart disease) exceeded infection as the leading cause of death in 8,549 pediatric chronic dialysis patients, accounting for 27% of deaths.2 An additional 6% of deaths in pediatric chronic dialysis patients were caused by CBVD. Infection was the second largest known cause of death in these patients, accounting for 20% of the patient deaths.2 A retrospective analysis of cardiovascular mortality in Medicare-eligible CKD Stage 5 patients who died at ages 0–30 years and who had participated in a USRDS special study as children (age 0–19 years) demonstrated that, of a total of 1,380 deaths between the years 1990 and 1996, 980 deaths were in the chronic dialysis patients. Cardiac causes accounted for 28% of all deaths in the dialysis patients and was second only to infection.14 Cardiac deaths occurred in 34% of 331 black compared with 25% of 649 white dialysis patients. For both the chronic dialysis and transplant groups, the risk of cardiac death increased by 22% with every 10-year increase in age.2 The dialysis arm of the North American Pediatric Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS) registry includes data on 4,546 patients <21 years of age. Of 205 deaths reported to the NAPRTCS dialysis registry, cardiopulmonary events were the second leading cause of death (44/205, 22%).19

In a retrospective USRDS study of 1,454 Medicare-eligible incident pediatric chronic dialysis patients identified from 1991 to 1996, 107 deaths were noted during the follow-up period (each cohort was followed for 3 years). Of those, 41 (38%) were cardiac-related.15 Cardiac deaths occurred in a greater percentage of blacks (5%) compared with whites (2%). The cardiac death rate did not decrease during the study period; (14.4 and 14.5 per 1,000 patient years for the 1991 and 1996 cohorts, respectively).

Similar mortality data have been reported for European and Asian pediatric CKD Stage 5 patients with cardiac deaths ranging from 30%–57% of all deaths.16 ,20–24 Overall mortality in Dutch children with CKD Stage 5 was reported to be 30 times higher than in the general Dutch age-and gender-matched pediatric population.16 Young age, black race, hypertension, and a prolonged period of dialysis have been associated with increased cardiac mortality in chronic pediatric CKD Stage 5 patients.

Cardiovascular Disease Events (Moderately Strong)

In the USRDS study noted above, CVD events were examined in the six incident pediatric chronic dialysis cohorts from 1991 to 1996.15 All patients were <20 years of age at the start of dialysis and each cohort was followed for up to 3 years. Of the 1,454 incident pediatric patients who started chronic dialysis between 1991 and 1996, 452 (31%) developed CVD.15 Arrhythmia was the most common cardiac event and it developed in approximately 20% of the study patients. Other cardiac-related events were vascular heart disease (VHD) (12%), cardiomyopathy (10%), and cardiac arrest (3.0%). The frequency of a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy was noted to double during the USRDS study period. Arrhythmias, including sinus tachycardia, premature ventricular contractions, and heart block have been reported in pediatric chronic dialysis patients.25–28 The 2002 USRDS Annual Data Report lists cardiac arrhythmia (hyperkalemia excluded) as the cause of death in 4% (14% of all cardiac-related deaths) of pediatric chronic dialysis patients for 1998 to 2000. Data on the incidence and prevalence of nonfatal MI, angina, and LVH were not reported.

Atherosclerosis

There is a paucity of data pertaining to atherosclerosis in children; this includes the general pediatric as well as the chronic pediatric dialysis populations. The 2002 USRDS ADR states that 10%–15% of prevalent pediatric chronic dialysis patients have a diagnosis of AHD. Musculoelastic intimal thickening is considered an early stage in the development of atherosclerosis and it has been reported in a small series of pediatric hemodialysis patients.29 In this study, a biopsy of the recipient iliac artery was performed at the time of kidney transplantation in 12 pediatric hemodialysis patients aged 11–17 years. Five (42%) arteries had fibroelastic intimal wall thickening, two (17%) had microcalcification in the intimal layer, and two (17%) had fibroatheromatous plaques (14). Six of the twelve patients had uropathy as the primary cause of CKD Stage 5 and atherosclerotic changes were present in the vessel sample obtained from all six of these patients. In contrast, only one of six patients with a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis as the cause of CKD Stage 5 had atherosclerotic changes. Serum phosphorus and the calcium-phosphorus product were higher in the uropathy group. The duration of CKD Stage 5 was, on average, 2 years longer in the uropathy group.29 (Weak)

Coronary artery disease

Limited data are available in pediatric patients. One group reported accelerated coronary artery disease at autopsy in 12 CKD Stage 5 patients <20 years of age.30 Intimal thickening was present in 50% of the CKD Stage 5 patients compared to 25% of 16 autopsy specimens obtained from pediatric patients without CKD Stage 5. Musculoelastic collagenous changes of the intima were present in 83% of CKD Stage 5 autopsy specimens compared to 25% of the control specimens. Indirect methods of determining coronary atherosclerotic disease have been studied in children. Coronary artery calcification has been studied by electron-beam computed tomography (EBCT) in 39 young adults (mean age 19 years) on chronic dialysis; the presence of coronary calcification was found in association with older age, a longer period of chronic dialysis, a higher mean phosphorus level, a higher daily calcium intake, and a higher mean calcium-phosphorus product.31,32 Confirmation of CAD in these patients was not done with the gold standard of coronary angiography. In addition, there were limited data available on traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the association of elevated coronary calcium. A study reported findings of soft-tissue calcification at autopsy in 72 of 120 (60%) pediatric patients with CKD Stage 5 treated from 1960 to 1983.33 Of the 120 patients, 54 (45%) were on chronic dialysis at the time of death. Soft-tissue calcification was present in 76% of the patients who had undergone chronic dialysis and 61% had severe systemic calcification. Coronary calcification by helical CT and intimal medial thickness by Doppler ultrasound have been studied in a cross-sectional analysis of 39 young adults (mean age 27 years) with CKD Stage 5 (13 chronic dialysis, 26 transplant) since childhood. Coronary artery calcification was present in 34 of 37 patients (92%) scanned, and did not correlate with worsening intimal medial thickness.34 Coronary artery calcification was associated with higher levels of C-reactive protein, plasma homocysteine, and intact PTH, as well as a higher calcium-phosphorus product.34 Coronary calcification may represent arteriosclerosis and not necessarily atherosclerosis in children on chronic dialysis. The distinction is usually made on autopsy material. Clearly, whether or not coronary artery and other vascular diseases are accelerated in children and young adults on chronic dialysis requires further study. (Weak)

Valvular heart disease/aortic valve calcification

A recent study examined the prevalence of aortic valve calcification in young adults who had experienced CKD Stage 5 since childhood. In this study, 30 of 140 Dutch patients who had onset of CKD Stage 5 at age 0–14 years (years 1972 to 1992) were on chronic dialysis (19 HD, 11 PD) at the time of cardiac evaluation in 1998 to 2000.35 Aortic valve calcification was determined by echocardiography. Aortic valve calcification was present in nine patients (30%) and by multiple regression analysis was associated with a prolonged period of peritoneal dialysis.35 At autopsy, it was found that four out of eight chronic pediatric dialysis patients had Moenckeberg-type arteriosclerosis and diffuse vascular and cardiac valve calcification.36 (Weak)

Hypertension/left ventricular hypertrophy

Hypertension is commonly seen in 49% of children with CKD37 and 50%–60% of patients on dialysis.38 Left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular dilatation, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction have been documented using echocardiography in studies of children on maintenance dialysis.39,40 Left ventricular hypertrophy is a known risk factor for CVD and mortality in adults on chronic dialysis but this has not been proven in children. The prevalence of LVH by echocardiography in 64 children on maintenance dialysis was 75%.40 Some authors report increased severity of LVH in pediatric hemodialysis compared to peritoneal dialysis patients.40,41 Established LVH has been reported at the initiation of maintenance dialysis in 20 of 29 (69%) patients aged 4–18 years.42 The results of this study implied that LVH begins to develop in children with earlier stages of CKD Stage 5. Left ventricular hypertrophy was found to progress in 14 of 29 patients who had LVH on initial evaluation. Progression in these patients was associated with increased systolic blood pressure. In the Litwin study of patient survival and mortality in 125 children from Poland on chronic dialysis, CVD accounted for 11 of 16 (69%) patient deaths.36 Five of the eleven patients who died of cardiac disease underwent autopsy and were found to have LVH. Screening for LVH by electrocardiogram in children is not recommended due to the very low sensitivity of the test.43,44 Echocardiogram is a more reliable measure of LVH in children and adolescents. (Weak)

Summary of pediatric clinical recommendations

Children commencing dialysis should be evaluated for the presence of cardiac disease (cardiomyopathy and valvular disease) using echocardiography once the patient has achieved dry weight (ideally within 3 months of the initiation of dialysis therapy). (C) Children commencing dialysis should be screened for traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia and hypertension. (C)

Children with VHD should be evaluated by echocardiography. Management of valvular disease should follow recommendations provided by the ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease VI.45 (C)

Children should be evaluated for the presence of cardiomyopathy (systolic and diastolic dysfunction) using echocardiographic testing. (C)

All dialysis units caring for pediatric patients need to have on-site external automatic defibrillators and/or appropriate pediatric equipment available. Automated external defibrillators may be used for children 1–8 years of age, and should ideally deliver pediatric doses and have an arrhythmia detection algorithm.46–48 (C)

Determination and management of children with diabetes should follow recommendations provided by the American Diabetes Association.49 (C)

Determination and management of blood pressure in children should follow recommendations by The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. 50 (C)

12.5.a: Optimal systolic and diastolic blood pressure should be <95% for age, gender, and height. (B)

12.5.b: Management of hypertension on dialysis requires attention to fluid status and antihypertensive medications, minimizing intradialytic fluid accumulation by (C):

Management of dyslipidemias for prepubertal children with CKD and CKD Stage 5 should follow recommendations by National Cholesterol Expert Panel in Children and Adolescents. Postpubertal children or adolescents with CKD Stages 4 and 5 should follow the recommendations provided in the KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Managing Dyslipidemias in Chronic Kidney Disease.51 (C)

All children on dialysis with anemia should follow the KDOQI Guidelines for Treatment of Anemia.52 (C)

There are no data available from large-scale studies of risk modification on which to make evidence-based recommendations. Two small studies in young adult chronic dialysis patients have shown coronary artery calcification to be associated with a higher calcium-phosphorus product. Although clinical practice guidelines for management of bone metabolism and disease in pediatric patients with CKD will be forthcoming, we recommend maintaining the corrected total calcium and phosphorus levels within the normal range for the laboratory used and the calcium-phosphorus product below 55 mg2/dL2 in children on chronic dialysis. (C)

Longitudinal studies to determine the magnitude of CVD and identify cardiovascular disease risk factors are needed in pediatric chronic dialysis patients, studies are needed to quantify the magnitude of risk, identify modifiable risk factors, and identify possible interventions. Cardiovascular risk factors are likely to be similar to those in adults and include high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, obesity, physical inactivity, anemia, calcium and phosphorus abnormalities, family history of CVD and its risk factors, genetics, inflammation, malnutrition, oxidative stress, hyperhomocysteinemia, and smoking (in adolescents).