Transplantation is not a cure. It is a state of CKD regardless of GFR or other markers of kidney damage.494 Management of children with a kidney transplant includes care of the graft, but also care of the complications of CKD.495,496 Children continue to require dietary modifications after transplantation to address nutrition-related issues. Early in the transplantation period, dietary management of hypertension, hyperkalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, and hyperglycemia are required to aid in the management of side effects of immunosuppressive drugs. Long-term interventions are needed to prevent or aid management of excessive weight gain/obesity, dyslipidemia, and steroid-induced osteoporosis. Children with CKD stages 2 to 5T require dietary management of protein and phosphorus in the same way as children with similar GFRs before transplantation. Continued assessment of nutrient intake, activity level, growth, laboratory values, and medications is suggested to ensure the best short- and long-term outcomes for children after transplantation.

10.1 Dietary assessment, diet modifications, and counseling are suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T to meet nutritional requirements while minimizing the side effects of immunosuppressive medications. (C)

10.2 To manage posttransplantation weight gain, it is suggested that energy requirements of children with CKD stages 1 to 5T be considered equal to 100% of the EER for chronological age, adjusted for PAL and body size (ie, BMI). (C) Further adjustment to energy intake is suggested based upon the response in rate of weight gain or loss. (C)

10.3 A balance of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and unsaturated fats within the physiological ranges recommended by the AMDR of the DRI is suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T to prevent or manage obesity, dyslipidemia, and corticosteroid-induced diabetes. (C)

10.4 For children with CKD stages 1 to 5T and hypertension or abnormal serum mineral or electrolyte concentrations associated with immunosuppressive drug therapy or impaired kidney function, dietary modification is suggested. (C)

10.5 Calcium and vitamin D intakes of at least 100% of the DRI are suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T. (C) In children with CKD stages 1 to 5T, it is suggested that total oral and/or enteral calcium intake from nutritional sources and phosphate binders not exceed 200% of the DRI (see Recommendation 7.1). (C)

10.6 Water and drinks low in simple sugars are the suggested beverages for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T with high minimum total daily fluid intakes (except those who are underweight, ie, BMI-for-height-age < 5th percentile) to avoid excessive weight gain, promote dental health, and avoid exacerbating hyperglycemia. (C)

10.7 Attention to food hygiene/safety and avoidance of foods that carry a high risk of food poisoning or food-borne infection are suggested for immunosuppressed children with CKD stages 1 to 5T. (C)

10.1: Dietary assessment, diet modifications, and counseling are suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T to meet nutritional requirements while minimizing the side effects of immunosuppressive medications. (C)

The short- and long-term effects of immunosuppressive medications present new and familiar nutritional challenges to children and their caregivers that change during the course of the posttransplantation period. Goals of nutrition in the immediate and short-term posttransplantation period are to encourage intake, promote anabolism and wound healing, maintain blood pressure control, and maintain glucose, mineral, and electrolyte balance. In the long-term stage of transplantation, nutritional goals are targeted to preventing chronic complications of immunosuppressive therapy, such as excessive weight gain/obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia and/or osteoporosis. Diet counseling should begin early to review the dietary prescription, nutrition-related medication side effects, and the nutrition care plan.

The first 3 to 6 months after transplantation can be very challenging for children and their caretakers, with many new routines and medications to learn. Because diets are advanced immediately after transplantation, it is recommended that patients be evaluated for appropriate energy, protein, carbohydrate, and fat intakes. If there is delayed normalization of kidney function, it is prudent to follow restrictions similar to those described for those with CKD stages 2 to 5 until kidney function normalizes. Over time, as immunosuppressant dosages decrease and their associated side effects recede, dietary modifications can be liberalized. Although many patients resist needing to follow a special posttransplantation diet, this is an appropriate time to instruct a healthy diet for age with a strong emphasis on regular exercise.

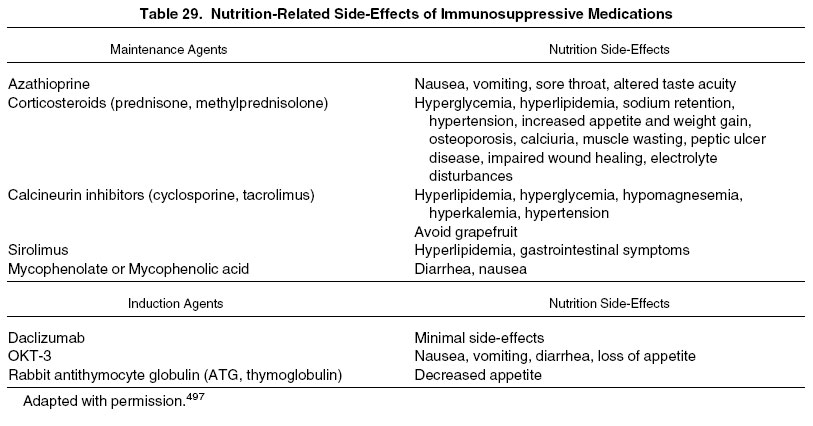

Table 29 lists nutrition-related side effects of currently used immunosuppressive agents in transplant patients.

Several of the side effects listed are transient and may last for only several weeks or months. Just as in the pretransplantation period, adaptation to some side effects often is possible, enabling a child to return to normal activities of living despite them. However, others present potentially life-long issues that will need to be considered for at least the duration of the transplant.

The frequency of nutritional assessment may be highest in the early posttransplantation period and decreases as the dosage and side effects of immunosuppressive medications are reduced. At a minimum, the frequency of nutritional assessment should be compatible with age- and stage-of-CKD–matched recommendations for children with CKD stages 2 to 5 and 5D (Recommendation 1, Table 1).

10.2: To manage posttransplantation weight gain, it is suggested that energy requirements of children with CKD stages 1 to 5T be considered equal to 100% of the EER for chronological age, adjusted for PAL and body size (ie, BMI). (C) Further adjustment to energy intake is suggested based upon the response in rate of weight gain or loss. (C)

There is no evidence that children who are transplanted have increased or decreased energy requirements compared with healthy children; however, excessive weight gain in children who underwent transplantation can occur due to improved appetite associated with feeling well, as well as appetite stimulation from corticosteroid immunosuppressive medications. Recent data from the NAPRTCS show a rapid increase in weight for all age groups in the first 6 months after transplantation, with children increasing an average of 0.89 SD in weight in the first year after transplantation, with relative stability in average standardized weight scores during the next 5 years.21 Whether a child is under- or overweight going into transplantation, calorie goals should be established after transplantation to achieve appropriate weight gain, maintenance, or loss.

Although most children with CKD are not overweight, recent data for growth and transplantation show that height and weight at the time of transplantation have increased and that more children are obese going into transplantation. The difference between mean pretransplantation height and weight SDS in 1987 was around 1 SDS, but had increased to 1.5 SDS in 2006 (web.emmes.com/study/ped; last accessed March 30, 2008), suggesting that children are now heavier for their height (overweight) at the time of transplantation. This is reflected in the increased prevalence of obesity in the pretransplantation setting from 8% before 1995 to 12.4% after 1995.21 Obesity may develop after transplantation, and weight gain may be more significant in those who were obese before transplantation.176 Mitsnefes et al176 found that the frequency of obesity doubled during the first year after transplantation.

Obese children going on to kidney transplantation have shown increased risk of mortality and decreased long-term kidney allograft survival.176,498 Additionally, in a retrospective review of pediatric kidney allograft recipients, children who were obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) at the time of transplantation had significantly worse 1-year allograft function compared with children who were not obese at the time of transplantation, but who became obese after 1 year and children who were not obese before transplantation or 1 year later.176 The difference remained significant after adjusting GFR to height. A greater incidence of posttransplantation hypertension in obese children may explain the observed association between pretransplantation obesity and decreased GFR.

In the general population, obese children are at risk of high total cholesterol levels (15.7% versus 7.2%), high LDL (11.4% versus 7.7%) or borderline LDL cholesterol levels (20.2% versus 12.5%), low HDL cholesterol levels (15.5% versus 3%), high TG levels (6.7% versus 2.1%), high fasting glucose levels (2.9% versus 0%), high glycohemoglobin levels (3.7% versus 0.5%), and high systolic blood pressure (9.0% versus 1.6%) compared with healthy-weight children.242 Given that the major cause of mortality in the CKD stage 5 population is cardiac related, the pediatric population, who are relatively young in the CKD process, stand to benefit from interventions to reduce obesity early in life.

For these reasons, it is important that patients and families be counseled on the potential risks of excessive weight gain and educated about appropriate dietary and exercise modification for weight control both before and after kidney transplantation.21 Interventional strategies for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity in the non-CKD population45 may be helpful.

Data from studies in the general population and the lack of adverse effects make compelling reasons for recommending that exercise, in combination with diet, be encouraged in transplant recipients to prevent and/or aid in the management of overweight, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Recommendations for children include encouraging time spent in active play (goal ≥ 1 h/d) and limiting screen time (television + computer + video games) to 2 h/d or less.173 For adolescents and adults, recommendations include moderate physical activity 3 to 4 times weekly (20- to 30-minute periods of walking, swimming, and supervised activity within ability), as well as resistance exercise training.499

10.3: A balance of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and unsaturated fats within the physiological ranges recommended by the AMDR of the DRI is suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T to prevent or manage obesity, dyslipidemia, and corticosteroid-induced diabetes. (C)

Dyslipidemia occurs frequently after kidney transplantation and promotes atherosclerosis; it may be associated with proteinuria in chronic allograft nephropathy, recurrent disease, obesity, and/or immunosuppressive medications. The reported prevalence of increased LDL cholesterol levels (>100 mg/dL) in pediatric kidney transplant recipients studied in the 1990s ranged from 72% to 84%.223,500-503 The risk and rates of posttransplantation dyslipidemia may differ based on the type of immunosuppression used, with lower prevalences reported with more recent protocols, including those that are steroid free.504-506 It is estimated that there are 20 cardiovascular events/1,000 patients per year after transplantation.507 Immunosuppressive agents, especially calcineurin inhibitors, directly contribute to side effects of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nephrotoxicity.508,509 It is generally accepted that dietary protein and carbohydrate intake do not influence CVD risk as much as fat intake. A study performed primarily to follow the effect of diet on plasma fatty acid levels in 29 children and adolescents concluded that diets containing protein intakes appropriate for age (RDA), a generous carbohydrate intake featuring a low glycemic load, and fat intakes less than 30% of total caloric intake were reasonable goals of diet therapy after transplantation.510 Another study of 45 patients did not find diet to conclusively explain the higher prevalence of dyslipidemia in their transplant patients compared with healthy controls.284 However, they recommended that all patients with CKD be counseled in a diet high in polyunsaturated fats and low in saturated fats. Children adhering to the Step II AHA diet (≤30% total calories from fat, <7% calories from saturated fat, 10% polyunsaturated fat, <200 mg/d cholesterol)511 had an 11% reduction in TG levels and a 14% reduction in LDL cholesterol concentration. In a study of the role of dietary intervention on metabolic abnormalities and nutritional status after transplantation, adults who followed a prescribed diet (AHA Step I Diet) and exercise regimen for the first year after transplantation showed significant improvements in weight, body fat, fasting glucose, and cholesterol levels; nonadherent patients experienced small, but insignificant, increases in the first 3 parameters and a significant increase in serum cholesterol levels.512 Therefore, a first-line treatment should include a trial of diet modification limiting saturated fat, cholesterol, and simple sugars. More current dietary recommendations aimed at the early prevention of CVD are available from the AHA.239 In children who resist overt dietary modification, healthy food preparation methods should at least be emphasized, including the use of such heart-friendly fats as canola or olive oils and margarines.

Glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia occur early after transplantation in association with surgical stress and corticosteroid and calcineurin inhibitor therapy, with serum glucose levels decreasing as immunosuppressant dosages decrease. Patients should be counseled to avoid simple sugars in the early posttransplantation period (the first 3 to 6 months) when steroid doses are highest and weight gain is most rapid. When blood sugar levels stabilize, it may still be necessary to restrict simple sugars to manage weight gain and hypertriglyceridemia. Posttransplantation diabetes mellitus occurs occasionally in pediatric kidney patients (2.6%) and is seen most frequently within the first year of transplantation.513 Children with a family history of diabetes are at higher risk of posttransplantation diabetes.

Previous recommendations for increased DPI in the early posttransplantation period are no longer warranted. Given the quick postoperative recovery of most children and the current steroid-free or rapid-steroid-taper protocols used, compensation for increased nitrogen losses, protein catabolism, and decreased protein anabolism associated with surgical stress and high-dose corticosteroid therapy is no longer justified.

10.4: For children with CKD stages 1 to 5T and hypertension or abnormal serum mineral or electrolyte concentrations associated with immunosuppressive drug therapy or impaired kidney function, dietary modification is suggested. (C)

The majority of children who underwent transplantation are hypertensive and receive antihypertensive medications throughout the immediate and follow-up posttransplantation period. Approximately 80% of children are hypertensive in the early posttransplantation period. This rate decreases to 65% to 73% at 2 years and 59% to 69% at 5 years after transplantation (web.emmes.com/study/ped; last accessed March 30, 2008). Dietary sodium restriction is indicated to aid in blood pressure management (see Recommendation 8).

Hyperkalemia in the immediate posttransplantation period occurs frequently in association with the medications cyclosporin and tacrolimus, especially when blood levels achieve or exceed therapeutic targets. Serum potassium levels should be monitored and a low-potassium diet should be implemented as indicated (see Recommendation 8).

Hypophosphatemia is a common complication seen in the early stage of kidney transplantation, occurring in up to 93% of adults during the first few months posttransplantation.514 Low serum levels occur in association with an increase in urinary phosphate excretion, decreased intestinal phosphate absorption, and hyperparathyroidism that persists beyond the pretransplantation period.514 Children with hypophosphatemia can be encouraged to consume a diet high in phosphorus (see Recommendation 5, Table 13); however, phosphorus supplements usually are required.121

Hypomagnesemia, a common side effect of calcineurin inhibitors, occurs early in the posttransplantation period. Increased dietary magnesium intake may be attempted; however, as in the case of hypophosphatemia, the amount of magnesium required to correct serum levels typically requires a magnesium supplement.

10.5: Calcium and vitamin D intakes of at least 100% of the DRI are suggested for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T. (C) In children with CKD stages 1 to 5T, it is suggested that the total oral and/or enteral calcium intake from nutritional sources and phosphate binders not exceed 200% of the DRI (see Recommendation 7.1). (C)

After transplantation, children are predisposed to progressive bone disease and osteoporosis for several reasons. They are likely to have preestablished metabolic bone disease associated with CKD. After transplantation, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and residual hyperparathyroidism may increase the risk of bone demineralization,121 with bone loss most rapid during the first year after transplantation.515 Osteopenia has been confirmed by using bone biopsy data and/or bone densitometry.516 Interpretation of DXA measurement of bone mineral density is complicated in children with delayed growth and maturation,121,517 and estimates of the perceived prevalence of moderate plus severe osteopenia vary according to analysis based on chronological age (42%), height-age (15%), or sex-matched (23%) reference data.516 Whether deficits in bone mineral density are reversible upon discontinuation of glucocorticoids is unclear. Pediatric kidney transplant recipients also are at increased risk of developing disabling bone disease, such as avascular necrosis and bone fractures. In addition, transplantation is part of the continuum of CKD, and progressive damage to the graft will result in bone mineral disorders similar to the effects of CKD in the native kidney.121

Because of these issues, it is recommended that serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, total CO2, and PTH continue to be monitored after transplantation (Table 30).121

To minimize bone mineral loss, daily supplementation at the level of the DRI for calcium and 800 to 1,000 IU of vitamin D has been suggested; however, there are no data for efficacy in children. Children with CKD stages 3 to 5T with bone mineral disorders should be managed according to established recommendations for nontransplantation children with similar GFRs (see Recommendation 7).

10.6: Water and drinks low in simple sugars are the suggested beverages for children with CKD stages 1 to 5T with high minimum total daily fluid intakes (except those who are underweight, ie, BMI-for-height-age < 5th percentile) to avoid excessive weight gain, promote dental health, and avoid exacerbating hyperglycemia. (C)

Good graft function after transplantation affects fluid and electrolyte balance. A high volume of fluid intake generally is prescribed to stimulate kidney function, replace high urine output, and regulate intravascular volume. Consumption of large volumes of fluids with high calorie, fat, or simple sugar content can contribute to obesity and exacerbate increased serum levels of glucose and TG. With the exception of children needing to gain weight, the majority of fluid intake should come from water, fat-free or low-fat milk, and sugar-free drinks. Increasing fluid intake frequently is challenging for children who followed a strict fluid restriction or were tube fed before transplantation. In some children, including infants and toddlers receiving an adult kidney, enteral hydration continues to be needed after transplantation.

10.7: Attention to food hygiene/safety and avoidance of foods that carry a high risk of food poisoning or food-borne infection are suggested for immunosuppressed children with CKD stages 1 to 5T. (C)

Immunosuppressed patients are more prone to develop infections, potentially including those brought on by disease-causing bacteria and other pathogens that cause food-borne illness (eg, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes). Many patients are given gastric acidity inhibitors after transplantation; these medications have been associated with increased risk of intestinal and respiratory infections in nontransplanted children.518 Of concern are the common symptoms of food-borne illness that include diarrhea and vomiting, both of which may lead to dehydration and/or interfere with absorption of immunosuppressive medications. Foods that are most likely to contain pathogens fall into 2 categories: uncooked fresh fruits and vegetables, and such animal products as unpasteurized milk, soft cheeses, raw eggs, raw meat, raw poultry, raw fish, raw seafood, and their juices. Although the risk of infection from food sources in immunosuppressed kidney transplant patients is unknown, it seems prudent that transplant patients be educated about safe practices when handling, preparing, and consuming foods (Table 31).519 Theoretically, food safety would be most important during periods when immunosuppression dosing is at its highest and liberalization or discontinuation could occur as immunosuppressant doses decrease.

The KDIGO Transplant Guideline is in development.

The majority of research in posttransplantation nutrition has been conducted in adults. There are no controlled studies of the effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density after transplantation.