Hypertension is common in CKD, and is a risk factor for faster progression of kidney disease and development and worsening of CVD. Some antihypertensive agents also slow the progression of kidney disease by mechanisms in addition to their antihypertensive effect.

1.1 Antihypertensive therapy should be used in CKD to:

1.1.a Lower blood pressure (A);

1.1.b Reduce the risk of CVD, in patients with or without hypertension (B) (see Guideline 7);

1.1.c Slow progression of kidney disease, in patients with or without hypertension (A) (see Guidelines 8, 9,10).

1.2 Modifications to antihypertensive therapy should be considered based on the level of proteinuria during treatment (C) (see Guidelines 8, 9, 10,11).

1.3 Antihypertensive therapy should be coordinated with other therapies for CKD as part of a multi-intervention strategy (A).

1.4 If there is a discrepancy between the treatment recommended to slow progression of CKD and to reduce the risk of CVD, individual decision-making should be based on risk stratification (C).

CKD is a world-wide public health problem, with increasing incidence and prevalence, high cost, and poor outcomes. The major outcomes of CKD are loss of kidney function and development of CVD. Increasing evidence indicates that the adverse outcomes of CKD can often be prevented or delayed through early detection and treatment.

Hypertension is both a cause and a complication of CKD; more than 50% to 75% of patients with CKD have blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg. In addition, hypertension is a risk factor for progression of kidney disease and for CVD. The goals of antihypertensive therapy in CKD are to lower blood pressure, reduce the risk of CVD, and slow progression of CKD.

The Joint National Committee (JNC) for Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure issues regular reports that are meant to provide guidance for primary-care clinicians. The seventh report (JNC 7), issued in 2003, suggests stratification of risk for CVD in individuals with high blood pressure to determine the intensity of treatment. Individuals at highest risk should receive most intensive treatment, including prompt pharmacological therapy, a lower blood pressure goal, and use of specific antihypertensive agents for "compelling indications," including CKD.5,5a

Hypertension is common in CKD, affecting 50% to 75% of individuals. The Work Group for this K/DOQI Guideline on Hypertension and Antihypertensive Agents in CKD proposes recommendations for all patients with CKD, whether or not they have hypertension. Guideline 1 reviews the goals of antihypertensive therapy; multi-intervention strategies for CKD; and possible discrepancies between goals of slowing progression of CKD and reducing CVD risk. It concludes with a review of key recommendations of the guidelines and compares the recommendations to those made by the JNC 7, as well as with previous reports by the NKF and ADA. Limitations, implementation issues, and research recommendations are covered in subsequent guidelines.

Definitions

Antihypertensive therapy includes lifestyle modifications and pharmacological therapy that reduce blood pressure, in patients with or without hypertension.

Lifestyle modifications include changes in diet, exercise, and habits that may slow the progression of CKD or lower the risk of CVD. These guidelines focus specifically on lifestyle modifications that lower blood pressure. Lifestyle modifications are discussed in more detail in Guideline 6.

Pharmacological therapy includes selection of antihypertensive agents and blood pressure goals. Antihypertensive agents are defined as agents that lower blood pressure and are usually prescribed to hypertensive individuals for this purpose. Other agents may also lower blood pressure as a side-effect. It is important to note that antihypertensive agents may have salutary effects on CKD and CVD in addition to lowering systemic blood pressure, such as reducing proteinuria, slowing GFR decline, and inhibiting other pathogenetic mechanisms of kidney disease progression and CVD. General principles of pharmacological therapy and target blood pressure for reducing CVD risk are discussed in Guideline 7.

"Preferred agents." Classes of antihypertensive agents that have beneficial effects on progression of CKD or reducing CVD risk, in addition to their antihypertensive effects, are defined as "preferred agents" for those conditions. Preferred agents for specific types of CVD are discussed in Guideline 7. In certain types of CKD, specific classes of antihypertensive agents, notably those that inhibit the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), are preferred agents for slowing progression of kidney disease. Thus, the guidelines recommend the use of specific classes of antihypertensive agents in certain types of CKD, even if hypertension is not present. These agents also reduce proteinuria and may be considered for this purpose as well. Preferred agents for CKD are discussed in Guidelines 8 through 10. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are discussed in Guideline 11, and diuretics are discussed in Guideline 12.

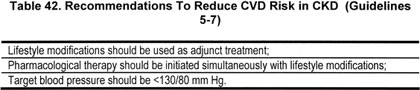

Patients with CKD are in the "highest-risk" group for CVD (Strong). Patients with CKD are at increased risk of CVD. Hypertension is a risk factor for CVD events in CKD. However, there have been few controlled trials to demonstrate the efficacy of blood pressure lowering to reduce the risk of CVD in CKD; therefore, the Work Group made recommendations for CKD based on extrapolation from evidence on the efficacy of antihypertensive therapy in the general population. Because of the high risk of CVD in CKD, the Work Group concluded that individuals with CKD should be included in the "highest-risk group" for implementation of antihypertensive therapy to reduce CVD risk. Table 42 shows recommendations from JNC 7 for the highest-risk group. Guideline 7 discusses the appropriate blood pressure target to reduce risk of CVD in the highest-risk group.

Some classes of antihypertensive agents are preferred in certain types of CKD (Strong). Most patients with CKD experience progressive GFR decline over time. Hypertension is a risk factor for faster progression of kidney disease. In addition, some other modifiable risk factors (proteinuria and activity of the RAS) are also affected by antihypertensive therapy. RCTs demonstrate that some classes of antihypertensive agents (notably, those that inhibit the RAS) are "preferred agents" for slowing progression of specific types of CKD. In addition, for some types of CKD, the blood pressure goal recommended for CVD risk reduction in high-risk groups has been shown to slow the progression of CKD. Thus, the Work Group recommended that antihypertensive therapy in CKD also be guided by the type of kidney disease. Table 43 shows general recommendations to slow the progression of CKD. Guidelines 8 through 10 discuss specific types of CKD.

Level of proteinuria and changes in the level of proteinuria may be a guide to modifications of antihypertensive therapy (Weak). Proteinuria is important in CKD for a number of reasons. It is a marker for kidney damage, a clue to the type (diagnosis of CKD), and a risk factor for faster progression of kidney disease and development of CVD, and it identifies patients who benefit more from preferred agents and a lower target blood pressure (Table 29). In addition, it has been hypothesized that changes in the level of proteinuria during treatment may be a surrogate outcome for kidney disease progression. The Work Group concluded that there is not yet sufficient evidence to confirm this hypothesis. However, it was the opinion of the Work Group that proteinuria should be monitored during the course of CKD, and that under some circumstances it would be appropriate to consider modifications to antihypertensive therapy, such as a lower blood pressure goal or measures to reduce proteinuria, such as increasing the dosage of preferred agents and selection of additional antihypertensive agents (Table 44). These measures are discussed in more detail in Guidelines 8 through 11. In general, these measures should be undertaken in consultation with a kidney disease specialist. The Work Group strongly recommended further research on this topic.

Approach to hypertension and use of antihypertensive agents in CKD (Strong). Figure 28 and Table 45 describe a the general approach recommended by the Work Group to integrate goals of lowering blood pressure, reducing CVD risk, slowing progression of kidney disease, and considerations regarding proteinuria.

Fig 28. General approach to hypertension and use of antihypertensive agents in CKD. Diamonds indicate decisions. Rectangles indicate actions. Superscripts refer to items listed in Table 45. A more detailed approach to decision-making and protocols for action are given in later sections.

Most patients with CKD will require multiple interventions to slow progression of CKD and prevent development or worsening of CVD (Strong). Most patients with CKD have multiple risk factors for progression of kidney disease and for development or deterioration of CVD.3,4 Optimal management of CKD requires coordination of antihypertensive therapy with other therapies, such as smoking cessation, lipid-lowering therapy, and management of diabetes, and other dietary and life-style modifications, which is best accomplished by a coordinated effort among practitioners, either in an individual or a team setting101,102 For example, the ADA recommends a multidisciplinary team approach for management of diabetes,6 and some studies show improved outcomes for diabetic kidney disease, using a multidisciplinary approach to deliver multiple interventions.103,104 The Work Group recommended coordination of antihypertensive therapy with other therapies for CKD and CVD as part of a multi-intervention strategy, using the resources of a multidisciplinary team, if available. A multidisciplinary team could include one or more of the following in addition to the physician: nurse practitioner, registered nurse, registered dietitian, masters prepared social worker, pharmacist, and physician assistant.

Individual decision-making is necessary to resolve discrepancies between recommendations for slowing CKD progression and reducing CVD risk (Strong). The Work Group accepted the principle that recommendations should maximize net health benefits for the target population (see Appendix 1). Having defined the goals for antihypertensive therapy to include slowing progression of CKD and reducing CVD risk in addition to lowering blood pressure, the Work Group searched for evidence in the target population for each clinical outcome. In general, there were few studies that adequately assessed both outcomes; thus, the Work Group made recommendations on the basis of separate studies on each outcome. This is a reasonable approach, if the recommendations to slow progression of CKD and reduce risk of CVD agree; however, if there is a discrepancy between recommendations, this approach may not be adequate. Other approaches, such as decision analysis, with or without regard to cost, could be useful to determine net health benefits in this situation.

In general, the Work Group found few examples of such discrepancies. However, it should be noted that most clinical studies (observational studies and controlled trials) do not provide an adequate framework for examining the possibility of conflicts. Nonetheless, there are inconsistent results among some recent controlled trials with regard to the beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors—aside from their antihypertensive effect—on slowing progression of CKD and reducing risk of CVD.105-107 Pertinent results will be discussed in later guidelines, but some general comments are appropriate here. In part, differences among studies may be related to differences in study populations and definition and ascertainment of endpoints. For example, studies on the progression of CKD have included patients with either markers of kidney damage (eg, diabetic patients with proteinuria) or decreased GFR (eg, most studies of nondiabetic kidney disease) and have carefully measured kidney function. On the other hand, studies of CVD risk reduction have generally excluded patients with elevated serum creatinine, did not routinely measure urine protein, and concentrated on ascertainment of CVD events. Thus, it is likely that studies on CKD enrolled patients at greater risk for progression of CKD than for CVD events and had greater statistical power to detect effects on CKD progression than on CVD events. Similarly, studies on CVD enrolled patients at greater risk for CVD events than for progression of CKD and had greater statistical power to detect effects on CVD events than progression of CKD. Hence, the Work Group generally restricted the interpretation of these studies to the primary outcome, as specified in advance by the authors. Differences in study design are discussed in an attempt to resolve discrepancies in findings and, in some studies, secondary outcomes are discussed. Overall recommendations are based on the sum of evidence, after taking into consideration all these factors.

In clinical practice, health-care providers must be concerned with all outcomes of care, not just a "primary outcome." Health-care providers caring for patients with CKD routinely encounter patients at high risk of both progression of CKD and CVD events and must make decisions about the implementation of recommendations about lifestyle modifications, blood pressure targets, and classes of antihypertensive agents that affect both outcomes. For example, should a patient with Stage 3 CKD due to Type 1 diabetes, a recent myocardial infarction, and Stage 1 hypertension be treated with an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, or diuretic? All classes of agents may be indicated, but if the blood pressure is too low, which agents should be used preferentially? Where recommendations are discrepant, health-care providers must make decisions to maximize the net health benefits for the individual patient. The Work Group recommends that such individual decision-making be based on risk stratification. In general, the selection of antihypertensive therapy should be directed to the clinical condition that is most likely to occur and that has the most serious consequences on overall survival and quality of life of the individual patient. Clinical practice guidelines cannot substitute for individual decision-making in patients with complex medical problems.

In addition to the JNC, several organizations have issued recommendations for blood pressure management in CKD. Previous recommendations by the NKF and other groups are listed in Table 46.1,15,108-121 Guidelines for CVD risk reduction in individuals without CKD are reviewed in Guideline 7. Guidelines for individuals with CKD are reviewed in Guidelines 8 through 10. In this discussion, the focus is on recommendations by JNC and ADA because these are the most widely used guidelines for treatment of individuals with hypertension and diabetes—the two most common causes of CKD. During the Work Group’s meetings, JNC 615 and ADA 2002115,116 were available.

Risk stratification (Table 47). JNC 6 suggested risk stratification of individuals with hypertension for therapeutic decisions.15 Although JNC 7 simplified this classification, the Work Group found the concepts useful in its deliberations. There is a spectrum of risk from very high to low, and patients were classified into three general risk categories. Patients at "low risk" (Group A) were defined as those without pre-existing CVD or target organ damage, without diabetes, and with no other risk factors for CVD other than hypertension. Patients at "high risk" (Group B) were defined as those without CVD or target organ damage, without diabetes, but with one or more with other risk factors for CVD. Patients at "very high risk" (Group C) were defined as those with CVD, target organ damage, or compelling indications, such as diabetes and CKD. Because there are few studies of antihypertensive therapy on CVD in CKD and because patients with CKD are in the highest-risk category for CVD, the Work Group recommends extrapolating the results from studies in the general population and other highest-risk populations to CKD (see Guideline 7).

Recommendations for low- and high-risk groups. JNC 6 and JNC 7 focus on therapeutic strategies to achieve target blood pressure level. The recommended goal of antihypertensive therapy in patients in risk groups A and B is to maintain SBP and DBP <140 mm Hg and <90 mm Hg, respectively. These definitions and goals do not differ according to age (among adults), gender, or race. Lifestyle modification is recommended for 6 to 12 months, followed by antihypertensive therapy if blood pressure remains above goal. The recommended initial antihypertensive agent is generally a diuretic, in combination with an ACE inhibitor, ARB, ß-adrenergic blocker, or a calcium-channel blocker if more than one agent is necessary to reach the target blood pressure.

Recommendations for the highest-risk group (Table 48). JNC 7 identifies the highest-risk group as those with "compelling indications" for antihypertensive therapy. Recommendations include prompt initiation of pharmacological therapy simultaneously with lifestyle modification, a lower blood pressure goal (<130/80 mm Hg), and antihypertensive medications specific to the comorbid conditions. In particular, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are recommended for patients with heart failure, diabetes, and CKD.5,5a

The 2003 ADA guidelines for treatment of hypertension in diabetic kidney disease recommend a blood pressure goal of <130/80 mm Hg and preferential use of ACE inhibitors in all diabetic patients with hypertension or CKD. ARBs are preferred in patients with macroalbuminuria and decreased GFR due to type 2 diabetes.6,121 A draft of the 2004 ADA guidelines available at the time the K/DOQI Guidelines contained similar recommendations.

Guidelines proposed by the NKF-K/DOQI Work Group on Hypertension and Antihypertensive Agents in CKD supersede those proposed by previous NKF groups1,3,4,112 and are largely consistent with recommendations by JNC 7 and ADA.