Careful initial evaluation and frequent re-evaluation are essential for effective treatment of hypertension and use of antihypertensive agents in CKD. Because CKD and hypertension are often present together and both are generally asymptomatic, Guideline 2 considers evaluations of patients with either condition.

2.1 Blood pressure should be measured at each health encounter (A).

2.2 Initial evaluation should include the following elements:

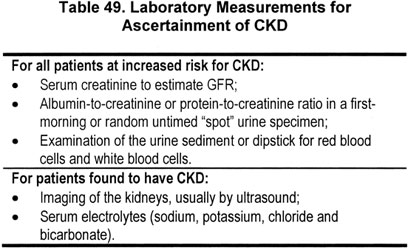

2.2.a.i Type (diagnosis), level of GFR, and level of proteinuria (Table 49) (A);

2.2.b Presence of clinical CVD and CVD risk factors (Table 50) (A);

2.2.c Comorbid conditions (A);

2.2.d Barriers to self-management, adherence to diet and other lifestyle modifications, adherence to pharmacological therapy (see Guidelines 5, 6,7) (B);

2.2.e Complications of pharmacological therapy (see Guidelines 7, 11-12) (A).

2.3 A clinical action plan should be developed for each patient, based on the stage of CKD (Table 51) (B).

2.4 Recommended intervals for follow-up evaluation should be guided by clinical conditions (Table 52) (C).

2.5 Patients with resistant hypertension should undergo additional evaluation to ascertain the cause (B).

2.6 Patients should be referred to specialists, when possible (Table 53).

Appropriate evaluation is the first step to achieving treatment goals. Since hypertension iscommon in CKD—and, conversely, CKD is common in hypertension—Guideline 2 includes evaluation for both CKD and hypertension. Several comprehensive guidelines to hypertension evaluation are readily available, and the principles described in JNC 7 are appropriate.5,5a With particular respect to CKD, general principles of the approach to the evaluation have been described in the K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for CKD (Guidelines 7, 13, and 15, and Part 9).1 Key elements of both evaluations will be reiterated here.

The question of whether particular demographic factors require modification of blood pressure management was addressed during the process of data abstraction of all studies of treatment that met the inclusion criteria. The literature searches were not restricted to studies in particular demographic groups, nor were searches focused on any demographic factors. Data abstractors were requested to comment on any results from analysis of subgroups or interaction terms suggestive of effect modification through demographic factors. In addition, the studies included in summary tables were reviewed in view of the prominent demographics of the populations studied, for example elderly or African-Americans. Separate summary tables were not developed.

Framework

The general principles of evaluation of the patient with hypertension as outlined in the JNC guidelines5,5a are appropriate for patients at all stages of CKD. Initial evaluation and re-evaluation in patients with CKD is extensive and may be performed over many visits with a variety of health-care providers working either alone or as part of a team. Health-care providers are encouraged to set up a routine system for efficiently conducting these evaluations. Some groups have found it helpful to utilize a multidisciplinary approach (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered dietitians, masters prepared social workers, pharmacists, physician assistants, and other professionals) for this purpose.

Initial Evaluation

The objectives of the evaluation are (1) detection of identifiable causes of hypertension, including CKD; (2) assessment of target organ damage, including CKD; and (3) identification of other CVD risk factors or concomitant disorders that may define prognosis and guide treatment (Table 54). With respect to patients with CKD, the high prevalence of CVD should be noted and should guide particular attention to CVD risk factors. In addition, nontraditional risk factors for CVD include the level of GFR and the presence of albuminuria or proteinuria.7

Initial evaluation of the patient with hypertension should include assessment for the presence of CKD (Table 55) (Strong).

Definition of CKD. CKD is defined as kidney damage, as confirmed by kidney biopsy or markers of damage, or GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for ≥3 months (Table 56).

Kidney damage. Kidney damage is defined as structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR. Markers of kidney damage include proteinuria, abnormalities of urine sediment, abnormalities in imaging tests, or abnormalities of blood or urine composition specific for certain syndromes (Table 57). Testing for proteinuria is outlined in detail later. A more detailed consideration of other markers is presented in the CKD Guidelines.

Several patterns of damage have been defined by study of kidney pathology; however, kidney biopsy is an invasive diagnostic procedure, which is associated with a risk, albeit very small, of serious complications. Therefore, kidney biopsy is usually reserved for selected patients in whom a definitive diagnosis can be made only by biopsy and in whom a definitive diagnosis would result in a change in either treatment or prognosis. In most patients, diagnosis is assigned based on recognition of markers of kidney damage, in association with well-defined clinical presentations and causal factors based on clinical evaluation.

Decreased GFR. The level of GFR is accepted as the best measure of overall kidney function in health and disease. The normal level of GFR varies according to age, gender, and body size. Normal GFR in young adults is approximately 120 to 130 mL/min/1.73 m2 and declines with age. A GFR level <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 represents loss of half or more of the adult level of normal kidney function, below which there is an increasing prevalence of complications of CKD.

GFR is difficult to measure, and recent guidelines recommend estimating the level of GFR using prediction equations (estimating equations) based on serum creatinine, age, sex, race, and body size. Commonly used equations in adults and children are shown in Table 58.

Table 59 shows the range of values of serum creatinine that correspond to an estimated GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, depending on age, gender, and race. This table highlights the observation that patients with serum creatinine level in the normal range can have CKD, and that minor elevations of serum creatinine concentration may be consistent with substantial reduction in GFR.

Figure 29 shows the level of GFR among individuals in the US population, estimated using the MDRD Study equation, based on age. The decline in GFR with age reflects the "normal" age-associated decline in GFR as well as the increased prevalence of kidney disease due to conditions associated with aging, such as diabetes and hypertension.

Fig 29. Age-associated decline in estimated GFR in NHANES III. GFR estimated from serum creatinine using MDRD Study equation. Age ≥20, N = 15, 600.

Traditionally, the age-related decline in GFR has been considered "normal." However, decreased GFR in the elderly requires adjustment in drug-dosing and appears to be an independent predictor of adverse outcomes, such as mortality and CVD. Thus, the definition of CKD is not modified based on age. This is analogous to blood pressure levels in the population and the definition and prevalence of hypertension. Blood pressure rises with age, but hypertension in the elderly is associated with adverse outcomes; thus, the definition of hypertension is not age-dependent, and the majority of elderly individuals are classified as having hypertension. Similarly, because of the age-related decline in GFR, the prevalence of CKD increases with age; approximately 17% of individuals greater than 60 years of age have an estimated GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Kidney failure (CKD Stage 5). Kidney failure is defined as either (1) GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, which is accompanied in most cases by signs and symptoms of uremia, or treatment by dialysis, or (2) a need for initiation of kidney replacement therapy (dialysis or transplantation) with GFR ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table 60). Approximately 98% of patients in the United States begin dialysis at GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2.127a Kidney failure is not synonymous with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). ESRD is an administrative term in the United States, based on the criteria for payment of health care by the Medicare ESRD Program: it applies to patients treated by dialysis and/or transplantation. However, ESRD does not include patients with kidney failure not treated by dialysis and transplantation, and payment for dialysis and transplantation varies among countries. Thus, although the term ESRD is in widespread use, and provides a simple operational classification of patients according to treatment, it does not precisely define a specific level of kidney function or a health outcome.

Initial evaluation of patients with HBP and CKD should include a complete description of CKD (Table 61) (Strong). The type of CKD is important, as some classes of antihypertensive agents are "preferred agents" for certain types of CKD, even in patients who are not hypertensive, eg, ACE inhibitors and ARBs for diabetic kidney disease and nondiabetic kidney disease with proteinuria, as discussed in Guidelines 8 and 9. The type of CKD and level of proteinuria may be an indication for a lower SBP goal. The level of proteinuria may be an indication for a higher dose of ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Complications of decreased GFR are important, as they may require additional therapy. The rate of decline in GFR is important to determine the frequency of follow-up.

Cause of CKD. Cause of CKD is important, since some antihypertensive agents are "preferred agents" for some types of CKD, even in patients without hypertension. Table 62 shows a simple classification of types of CKD and the proportion of patients with new onset of kidney failure from these diseases.17

History of CKD. Initial assessment should include a complete medical history, including history of and severity of CKD (Table 63); known duration and levels of HBP; evidence of CVD; presence of other comorbid conditions such as diabetes and dyslipidemia; symptoms suggesting identifiable causes of hypertension in addition to CKD; extracellular fluid volume status; lifestyle issues which may impact on CKD and blood pressure management; prescribed and other medications (including NSAIDs, herbal remedies, and illicit drugs); results of current and prior antihypertensive therapy; and psychosocial and environmental factors.1 For additional diagnostic clues in children, see Guideline 13.

Physical examination. A complete physical examination should be performed, to assess severity of hypertension, presence of end-organ damage, and extracellular fluid (ECF) volume (Table 64).5,15 Most kidney diseases do not cause alterations in the physical examination. Infrequently, secondary causes of hypertension other than CKD can be detected. Renal artery disease (see Guideline 4) can coexist with other types of CKD.

Laboratory tests. Routine laboratory tests are also recommended. These should include those tests that are recommended for the evaluation of CKD (Table 65). In particular, prediction equations should be used to estimate GFR from serum creatinine in adults123-125 and children126,127, and a spot urine sample should be obtained to estimate albuminuria or proteinuria.1 Of note, JNC 7 concurs with measuring serum creatinine to estimate GFR, but considers testing for albuminuria or proteinuria as "optional."5,5a The Work Group recommends that all patients with hypertension be tested for albuminuria or proteinuria, since CKD is both a cause and a consequence of hypertension, and since CKD is a risk factor for CVD.

In addition, basic blood chemistries should be obtained, as well as a glucose and fasting lipid panel. All patients should also have a 12-lead EKG, to screen for LVH. Optional additional tests may include thyroid-stimulating hormone, calcium, and uric acid levels.5,5a

Proteinuria. K/DOQI Guidelines for CKD recommend testing for albuminuria in all patients at increased risk for CKD.1 Current guidelines define albuminuria as spot urine albumin to creatinine ratio >30 mg/g in both men and women,1,6,128,129 although some studies have suggested different cut-off values for men and women.18,19 The Work Group has modified this recommendation for the purpose of treatment of hypertension and use of antihypertensive agents since, as described in Guidelines 8 and 9, decision-making is based on quantification of albuminuria (spot urine albumin to creatinine ratio >30 mg/g) in diabetic patients, and on quantification of proteinuria (spot urine total protein to creatinine ratio >200 mg/g) in nondiabetic patients.

An algorithm for further ascertainment of proteinuria is shown in Fig 30. A spot urine sample should be tested using either a standard dipstick in patients without diabetes (left side) or an albumin-specific dipstick in patients with diabetes (right side). Proteinuria should be quantitated in patients with a positive test; a spot urine sample should be tested for total protein to creatinine ratio in patients without diabetes or albumin to creatinine ratio in patients with diabetes. The level of proteinuria is important to ascertain as it will help determine if there is a preferred agent for the management of hypertension. Follow-up of elevated urine protein levels is discussed in Guidelines 8 through 10.

Fig 30. Evaluation for proteinuria for evaluation of hypertension and use of antihypertensive agents in CKD. Figure is modified from CKD Guideline 5, Fig 57, because criteria for selection of preferred agents in nondiabetic kidney disease are based on measurements of urine total protein rather than urine albumin.1

Other laboratory tests. The rationale for other laboratory tests is to identify the cause of CKD, in particular causes of nondiabetic kidney disease (Guideline 9). The interpretation of urinalysis, serum electrolyte concentrations, and imaging studies in the diagnosis of type of CKD are discussed in CKD Guidelines (Guideline 6 and Part 9).1 Imaging studies should be performed to detect obstruction of the urinary tract, polycystic kidney disease, stones, or congenital disorders.

Coexistence of renal artery disease and other identifiable causes of hypertension. Once the initial data are available for evaluation, consideration should also be given to the presence of renal artery disease (RAD) or other identifiable causes of hypertension, in addition to CKD. These include primary hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma, thyroid disease, aortic coarctation, Cushing syndrome, and hyperparathyroidism.

Evaluation for RAD is challenging, particularly in patients with CKD. The approach is based on identification of clinical factors associated with a higher risk of RAD and estimation of the probability of RAD using prediction equations (Guideline 4). In all cases, however, the risk of toxicity from angiographic contrast and revascularization procedures must be considered when assessing the risk/benefit ratio of detection and intervention. If available, gadolinium should be substituted for standard contrast agents in patients with CKD.

Complications of decreased GFR. Table 66 lists clinical problems and additional evaluation for patients with GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Rate of GFR decline. The normal mean age-related decline in GFR for adults greater than 20 to 30 years of age is 1 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year. For individuals with GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, the interval until kidney failure would be approximately 10 years or less if the rate of decline is ≥4 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year (Table 38). CKD Guideline 13 identifies a GFR decline of ≥4 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year decline as "fast".1 In practice, it can be difficult to estimate the rate of decline in GFR unless the rate is "fast" or the follow-up interval is long.

Risk factors for faster GFR decline. CKD Guideline 13 reviews risk factors associated with progression of kidney disease, as judged by faster rate of GFR decline or increased risk of developing kidney failure.1 The rate of progression is related to the type of kidney disease and, in addition, to nonmodifiable and modifiable patient characteristics, irrespective of the type of kidney disease (Table 67). Modifiable factors associated with blood pressure management include hypertension and proteinuria. Other mechanisms, such as increased activity of the renin-angiotensin system, may contribute to kidney disease progression through mechanisms in addition to hypertension and proteinuria.

Risk factors for acute GFR decline. GFR decline may be variable. Acute decline in GFR may be superimposed on CKD (Table 68). CKD Guideline 13 discusses risk factors for acute decline in GFR.1

The initial evaluation should include ascertainment of clinical CVD and CVD risk factors (Strong). As reviewed in Guideline 1, patients with CKD are considered in the highest-risk group for CVD. High priority must be given to identification and treatment of CVD, as well as to identification and treatment of CVD risk factors other than HBP and CKD (Table 69).

The initial evaluation should include ascertainment of comorbid conditions (Strong). Attention must be paid to the presence of comorbid conditions, particularly those conditions that affect kidney function or blood pressure; require treatment with antihypertensive agents; require treatment with medications that raise blood pressure; constitute an absolute or relative contraindication to specific classes of antihypertensivetherapy; require additional diet or lifestyle modification; or require diet modifications or medications that interact with antihypertensive medications (Table 70). For example, many commonly used drugs may increase blood pressure or interfere with the efficacy of antihypertensive agents.5,15

Initial evaluation should include assessment of barriers to self-management (see Guideline 5), adherence to diet and other lifestyle modification (Guideline 6), and adherence to pharmacological therapy (Guideline 7) (Moderately Strong).

Initial evaluation should include development of a clinical action plan, based on the stage of CKD (Moderately Strong).

Among individuals with CKD, the stage of disease and the clinical action plan is based on the level of GFR (Table 51), irrespective of the cause of kidney disease. The action plan for stages of CKD is discussed in more detail in NKF- K/DOQI Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease.1 Evaluation of hypertension and treatment with antihypertensive agents is part of the action plan for all stages of CKD.

Follow-Up Evaluation

Follow-up evaluation includes many of the same elements as the initial evaluation. Particular attention is given to adherence to lifestyle modifications and pharmacological therapy, the level of blood pressure, volume status, GFR, proteinuria, serum electrolytes, adverse effects of and interactions with antihypertensive medications, complications of CKD, CVD risk factors in addition to hypertension, CVD, and comorbid conditions.

Frequency of follow-up evaluation after initiation of antihypertensive agents depends on level of blood pressure, GFR, and serum potassium (Weak). In general, follow-up should be in approximately 4–12 weeks if SBP is 120–139 mm Hg, GFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and serum potassium ≤4.5 mEq/L for patients prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB or >4.5 meq/L in patients prescribed a thiazide or loop diuretic. Follow-up should be considered sooner if SBP, GFR, or serum potassium is not within these ranges (Table 52).

After a stable blood pressure management regimen is achieved, follow-up should be every 6–12 months, and more frequently if GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, if GFR decline is fast (≥4 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year), or in the presence of risk factors for faster GFR decline, risk factors for acute GFR decline, or comorbid conditions (Table 52).

Resistant Hypertension

Resistant (refractory) hypertension should be considered if the blood pressure goal cannot be achieved in patients who are adhering to an adequate and appropriate three-drug regimen that includes a diuretic, with all three drugs prescribed in near-maximal doses (Moderately Strong). There are many factors which can lead to inadequate responsiveness to therapy. These are detailed in Table 71, as modified from JNC 7.5,5a In patients with CKD, deterioration in blood pressure control may be a clue to progression of kidney disease. These patients are also at high risk for volume-dependent hypertension; failure to increase diuretic therapy as CKD worsens can often aggravate blood pressure control. Some patients with resistant hypertension can develop hypertensive crisis (defined as severe elevations in blood pressure [>180/120 mm Hg] with or without impending or progressive organ dysfunction). Treatment of these conditions is beyond the scope of these guidelines and is discussed in JNC 7.5,5a

Referral to Specialists

Patients should be referred to a kidney disease specialist for GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Moderately Strong) or to kidney disease or other specialists for indications as listed in Table 53 (Weak). In general, the Work Group recommended referral to specialists for complex or serious clinical conditions was based on opinion. However, recent observational studies in adults document better outcomes after the initiation of dialysis in patients who were referred to nephrologists earlier before onset of kidney failure.130-132 Thus, the recommendation for referral of patients with GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 to a kidney disease specialist was based on moderately strong evidence. The Work Group considered that all children should be referred to a pediatric kidney disease specialist, if possible.

Additional Considerations for Special Populations Other Than Children

The general guidelines in this document should be followed in all groups. There are no needed modifications for special populations (Moderately Strong). Epidemiological data suggest that older age, male gender, and non-Caucasian race are risk factors for faster loss of kidney function in CKD (see K/DOQI CKD Guideline 9)1, and that older age, male gender, and Caucasian race are risk factors for CVD.

Control of blood pressure has been shown to slow the progression of kidney disease and reduce CVD risk in all demographic groups studied. Regarding age-related loss of kidney function, epidemiological studies suggest that hypertension is a risk factor for acceleration of CKD.93 There are no specific interventional studies of hypertension control and its effect on age-related decline in GFR, though many studies have documented the value of therapy in reducing cardiovascular risk in the elderly.15,107,133,134 Short-term studies using proteinuria as a surrogate endpoint have shown beneficial effects of ACE inhibitor therapy in various demographic groups, including African-Americans,135 as well as in patients with various forms of kidney disease including HIV-associated nephropathy136 and sickle cell nephropathy.137 Gender does not significantly affect the beneficial effects of antihypertensive therapy.138-140

Fig 31. Evaluation of Patients With CKD for Treatment of Hypertension and Use of Antihypertensive Agents

Figure 31 and Table 72 summarize the initial and follow-up evaluation.

The risks of hypertension and the need for prompt recognition and evaluation in the general population are well documented. Far less evidence specific to the CKD population is available, and it must be acknowledged that many of the major hypertension trials upon which JNC guidelines are based specifically excluded patients with kidney disease. Nevertheless, the CVD and CKD progression risks are well documented, and so it seems only prudent to follow accepted recommendations in this patient population.

Effective evaluation and treatment of hypertension is a challenge, and particularly so in the CKD population. Insurance coverage and financial resources will frequently dictate the degree of laboratory evaluation that may be performed. Fortunately, the most important basic lab tests (urinalysis, chemistry panel) are relatively inexpensive, as are a number of effective generic antihypertensive medications. Lifestyle issues that complicate treatment of hypertension are often occult and difficult to elicit. As mentioned above, the toxicity to the kidney of angiographic dye may make the decision whether to look for renal artery stenosis particularly difficult.

In general, there are no specific implementation issues for any particular population subgroup. However, in choosing initial and subsequent pharmacological agents, known differences in drug efficacy should be noted. For example, diuretics are particularly effective in the elderly and in African-Americans.15 ACE inhibitors are recognized to be slightly less effective at reducing HBP in African-Americans than in Caucasians, and yet have been shown to be effective in slowing the progression of kidney disease in this group.141 In all groups, it should be recognized that effective blood pressure control will require multiple agents, and therefore minor differences in efficacy of one class or the other can be easily circumvented by addition of other drugs.

The current clinical questions related to essential hypertension are all areas that require further research in CKD. These questions cannot be answered unless patients with CKD are included in large randomized trials. Areas for investigation include: